Bix’s House and the NRHP

The National Register of Historic Places, a branch of the Department of Interior, is the Nation’s official list of cultural resources worthy of preservation. Among the 80,000 properties listed in the Register, are National Historic Landmarks, Lighthouses, Libraries, Schools, and Mills. The National Register also includes about 15,000 houses across the United States. One of these is the house at 1934 Grand Avenue, Davenport Iowa.

Of course, this is the house where Bix was born. The petition to include Bix’s house in the National Register was filed by Dan Newby, owner of the property at the time, on May 17, 1977. The house was entered into the register on July 13, 1977, reference number 77000554. Oddly enough, the name Bix does not appear in the official name of the property. It is listed as the Leon Bismark Beiderbecke House. To qualify for inclusion in the National Register, the property must be of special significance to the Nation, the State, or the community. To be sure, Bix’s house qualifies on all counts. Bix’s musical genius transcends Davenport, Iowa, and even the United States, as witness the number of biographies written abroad and the number of reissues on LP’s and CD’s of Bix’s recordings in Italy, France, Germany, and England.

The house is owned by Pupi and Antonio Avati, who directed and produced the film Bix: An Interpretation of a Legend.

International Jazz Hall of Fame

In November 1997, Bix Beiderbecke was inducted into the International Jazz Hall of Fame (IJHF). The following quote is taken from their web page:

The primary mission of the IJHF is to preserve and perpetuate the sophisticated, multifaceted art form that is American jazz.

From 1972 to 1991, the IJHF was part of the Charlie Parker Memorial Foundation. In 1991, it was incorporated as a nonprofit organization. Since 1977, the IJHF has inducted several jazz giants into its ranks, among them I cite Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Ella Fitzgerald, and Charlie Parker. At the Induction Award Ceremonies in Tampa, Florida, on November 20, and 21, 1997, in addition to Bix, Earl Hines, Coleman Hawkins, Jelly Roll Morton, and Django Reinhardt, among others, were inducted. I do not have information about the format of the ceremonies. But I imagine that each inductee is given a citation. If anyone has detailed information about Bix’s induction, I would be grateful if he/she could make the information available to me.

Bix Beiderbecke, One of Down Beat’s “Immortals of Jazz”

In the August 1, 1940 issue of Down Beat magazine, Bix Beiderbecke was named for the “Immortals of Jazz” honor. Other jazz musicians in the group of “Immortals” are Fats Waller and Jelly Roll Morton. The announcement and write-up follow.

Note the following corrections to errors in the text:

- Bix attended Davenport High School for three and a half years.

- Bix left Whiteman in 1929.

- Bix did not play with the Casa Loma Orchestra.

- Bix died in his apartment in Sunnyside, Queens, on August 6, 1931.

Steve Hester kindly sent a list of all musicians honored by the Down Beat “Immortals of Jazz” award. The first to receive the award was Red Nichols (Sep 1939); the last was Wingy Manone (Aug 1941).

Bix’s Cornet.

In February 1927, Bix bought what is commonly known today as Bix’s cornet, a gold-plated Bach Stradivarius serial number # 0620, bell-mandril # 106, with “Bix” engraved on the bell. It is currently displayed in a glass case in the Putnam Museum in Davenport. The cornet took a circuitous route in going from Bix’s hands to the Museum. At various points in time, the cornet was in the Midwest, in the East, and in the West.

Initially, the cornet was brought back from New York to Bix’s house in Davenport by Aggie (Bix’s mother) and Burnie (Bix’s brother) when Bix died. At one point, the cornet was given to Burnie and then transferred to Bix’s sister, Mary Louise Shoemaker. Mary Louise, who was living in Boston at the time, entrusted the cornet to the late Robert Mantler (who worked for Victor Records) to have it sent out for repairs and restoration. Mantler kept it in his possession for a number of years until, under a court order, it was returned to the Shoemaker family in 1976. The family kept the cornet until Eva and Bob Christiansen (from California), purchased it from Bix Shoemaker, Marie Louise’s son. The contract worked in 1990, stipulated that the cornet would be in the possession of the Christiansens for a period of five years, after which time the Christiansens were to donate Bix’s cornet to the Putnam Museum. Bob and Eva took possession of the cornet in Boston, MA on July 19, 1992.

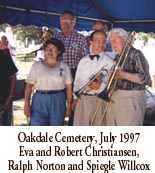

Five years later, the Christiansens donated the cornet to the Museum. The transfer took place at the 26th Annual Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Festival (1997). On the Saturday morning of the Festival (July 26), Ralph Norton played Bix’s cornet at Bix’s graveside. Eva and Bob Christiansen were present. Spiegle Willcox joined Raph Norton and the Varsity Ramblers in playing several of Bix’s favorites.

In the picture on the right, Ralph is holding Bix’s cornet. Eva and Bob are on his right, and the legendary Spiegle is on his left.

On Saturday evening, the official ceremony took place on the bandshell stage at LeClaire Park. Eva and Bob handed the cornet to Chris Reich, director of Davenport’s Putnam Museum, who accepted it on behalf of the community. The audience first watched silently, but then broke into enthusiastic applause. Bix’s horn had finally found its permanent home.

I strongly recommend four references about the topic of Bix’s cornets:

- In Bix, The Leon Bix Beiderbecke Story by Philip R. and Linda K. Evans, there is a detailed description of Bix’s cornets, followed by an instructive discussion of the cornets by Ralph Norton.

- Joe Giordano provides a detailed account of his visit to Davenport in the November 1976 issue of Jersey Jazz. Joe, Bix Shoemaker, Peter Shoemaker (Bix Shoemaker’s nephew), and Dave (Bix Shoemakers’ son’s brother-in-law) drove from Newark, NJ to Davenport, IA to attend the 1976 Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Festival. They brought with them Bix’s cornet. Joe describes his meetings in Davenport with Don O’Dette (President of the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Society at the time), Esten Spurrier (Bix’s friend from high school days), and Gerry Jest (a Canadian who helped Brigitte Berman with her documentary film about Bix) and relates some of their discussions about Bix’s cornet.

- Jim Arpy has a very informative article about the return of Bix’s cornet to Davenport in 1997 at http://www.qconline.com/bix/horn.html

- There is an account of a gathering at the Christiansen entitled The Night They Played Bix’s Horn at http://www.shellac.org/wams/wcornet1.html

I thank Joe Giordano for helpful discussions and his generous gift of a copy of his article. I am grateful to Frank Manera for providing additional information about the whereabouts of the cornet. The image of the cornet is courtesy of Enrico Borsetti. Last, but not least, I am indebted to Robert Christiansen for his gracious and detailed answers to my unending questions.

The Plaque at 1600 Broadway

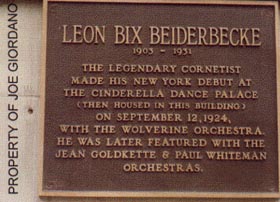

The building at 1600 Broadway in New York City (the northeast corner of Broadway and 48th Street) is currently owned by Sherwood Equities. It is an approximately twelve-story office building that is not in the best of condition. During the 1920s, the building housed, on the second floor, the Cinderella Dance Palace also known as the Cinderella Ballroom. The Club New Yorker, where Adrian Rollini’s band (including Bix) played in October 1927 was also located in this building.

September 12, 1924, marked the debut of the Wolverine Orchestra (with Bix) in New York City at the Cinderella Ballroom. This historic event was commemorated in April 1975 with the unveiling of a plaque. A photograph of the plaque is shown on the left.

What follows is an account of the origin of the plaque. The information is taken from an article published by Joe Giordano in the October 1987 issue of Jersey Jazz. The idea of a Bix plaque at 1600 Broadway came to Paul Hutcoe (then in New York City, presently in Maryland) when he learned that a concert in commemoration of Bix’s music was to be held in Carnegie Hall in April 1975. Several of the surviving musicians who had played with Bix were going to be present at the concert. Paul thought that Bix’s fellow musicians could be invited to the unveiling of a plaque. With jazz musicians of the caliber of Bill Challis, Paul Mertz, Chauncey Morehouse, Bill Rank, and Spiegle Willcox, Paul imagined that the event could have even more historical significance. Paul paid for half the cost of the plaque and received contributions from Jack Bradley (who was in charge of photographing the event), Reagan Houston (retired army officer and Bixophile), Bill Donahoe of the “Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Band” and other individuals that Paul could not recall. The plaque was unveiled on April 2, 1975. In addition to the musicians mentioned above, Jeff Atterton and Virginia Horvath Morehouse were present.

The plaque remained on the building for many years. However, a letter from a reader – F. Tauber – to the New York Daily News issue of July 11, 1987, pointed out that “A few months ago, because of painting, a plaque commemorating Leon (Bix) Beiderbecke was removed from the entrance to the Screen Building at 1600 Broadway. The paint has long since dried. Where is the plaque?” Joe Giordano tried to contact the building manager but was unsuccessful. He decided then to organize a letter-writing campaign to have the plaque remounted. In his article in Jersey Jazz, Joe asked all readers to write to the manager of the building at 1600 Broadway and “demand that the plaque be put back.” The campaign was successful, witness the fact that the plaque was remounted in 1987. The plaque remained on the building until, at least, two years ago. At that time, Joe Giordano took his friends Eva and Robert Christiansen, who were visiting New York from California, to see the plaque. Unfortunately, the plaque is no longer on the building. In conjunction with the memorial event on August 6, 1999, in front of Bix’s last residence in Sunnyside, Queens, I went to New York City and noticed that the plaque was gone again. Maybe it is time to follow Joe Giordano’s example and start a letter-writing campaign. I will make some inquiries and keep readers informed. I am indebted to Joe Giordano for his invaluable help and for his patience in answering my questions.

I am grateful to Don Robertson, editor of Jersey Jazz, for a gift of a copy of Joe’s article.

A Discussion of Cornet Mouthpieces and Conn Victors Played by Bix

Guest Column by Enrico Borsetti. The first and foremost consideration, when comparing or contrasting cornet playing with trumpet playing, is purely stylistic. One can play the trumpet in a “cornet” style, or play the cornet in a “trumpet” style if the distinction between the two is understood by the player (although the former may be more effective than the latter). One must remember that the true cornet consisted of an almost entirely conical tubing that was mated to a conical mouthpiece which bore more resemblance to the French horn mouthpiece than to the bowl-shaped trumpet mouthpiece. The early cornet which combined the conical tubing with the conical mouthpiece, produced, in the hands of a good player, a beautiful, velvety, non-directional tone but with very little carrying brilliance. The “modern” cornet, which has been given a greater percentage of cylindrical tubing to increase its projection, is usually mated to a bowl-shaped mouthpiece like that of a trumpet. This results in very little distinction between the tone quality of the cornet and the trumpet. T

here is a contingent of traditional jazz players who insist upon the correctness of the cornet, but I must note that I have never found a “modern” cornetist, playing in this genre, using a true cornet V-shaped mouthpiece. Without exception, they all use the bowl-shaped mouthpiece. Bowl-shaped cornet mouthpieces were introduced by Vincent Bach in the mid-20s; they are longer (7 cm) and give more projection and brilliance to the tone. Vintage cornet mouthpieces (not Bach) prior to 1930 like Conn, York, Boosey, Holton, Buescher, and King, are lighter in weight; they are all V-shaped and between 5,2 and 6,2 cm in length (I have a drawer full of vintage and current mouthpieces). I realize that the size of Bach mouthpieces varies with years: a vintage Bach trumpet mouthpiece number 5 or 7 is smaller in size and diameter than a 5 or a 7 made today; also the “throat” and the shape of the backbore are different, as I have measured using a digital caliper and other proper tools. I personally checked Bix’s Bach Stradivarius cornet ten years ago (thanks to Bob and Eva Christiansen) and it comes with a vintage 7 Bach mouthpiece (not a 7A as someone said in the forum).

About the matter “How many Conn cornets did Bix own?’ Certainly, models 80A and 81A. This horn has been in the market since the late 1910s with CONN “NEW WONDER” stamped on the bell. Around 1920/21, it was renamed VICTOR. In more than three years, on many items posted on eBay, I saw some bells engraved with “VICTOR NEW WONDER”. On some others just there was no engraving, only the factory name. Victor’s were in production until the early ’60s. Vintage cornets have the Bb/A quick change mechanism. I have seen others without it, especially the ones made from the 30s on. The most expensive models had full, custom engravings on the inside and outside of the bell, and gold plating. The peculiar difference between a NEW WONDER and a VICTOR is in the valve bottom caps: the NEW WONDER has funnel-shaped ones, and the VICTOR has flat ones with mother pearl inlay. The NEW WONDER came out also in another version Bb/C, with a rotary valve on bell tubing. In the early days, the factories of wind instruments made horns with different A of reference, standard A at 440 Hertz, A for other countries like Canada or New Zealand at around 452 Hertz. You could purchase a cornet or a trumpet which could be played in both countries since the case included extra slides, like the 81A. It was easy for brass, unlike saxophones, to quickly have a longer or a >shorter instrument just by changing the slides. On the bottom of the sax was stamped an L or an H meaning low pitch or high pitch. Back to Bix, if you take a look at the photos in the Sudhalter and Evans or Evans and Evans books you can notice different cornet cases and cornets Bix used to have. The better photo with Bix holding the cornet is the one in Davenport on August 30th, 1921, holding an 80A. If you have the Venuti/Lang Columbia C2L 24 two LP’s set “STRINGIN’ THE BLUES”, in the inside book there’s a very large foto of Rollini’s New Yorkers from which you can see Bix holding an 81A model, the mouthpiece rim is closer to the bell curve, the lead pipe is shorter. Bix played on a V-shaped mouthpiece for sure, if not the Conn that came in the cornet case.

For images of Enrico Borsetti’s cornets, go to cornet images:

- Victor 80A (golden)

- Victor 80 A (golden)

- Victor 80A (golden)

- Victor 80A (silver)

- Victor New Wonder

- Victor New Wonder and Close-up 1

The Summer of 1926 at the Blue Lantern Casino at Hudson Lake

Bix played with the Frank Trumbauer orchestra at the Arcadia Ballroom in St. Louis during the period September 8, 1925- May 3, 1926. This was a very good year for Bix for several reasons.

First, it was a year of stability. During the 10 years, beginning in 1921 when Bix left his home in Davenport and ending in 1931 when he died in New York, this was the longest period of time that Bix spent in one particular location.

Second, his professional life was regular, with daily rehearsals and appearances at the Arcadia Ballroom.

Third, his personal life was fulfilled through his close relationship with Ruth Shaffner. When Bix and Tram left St. Louis, they joined the Jean Goldkette Orchestra. In May 1926 Tram led a Goldkette unit at Hudson Lake, Indiana. The engagement lasted from May 22 to August 30, 1926. The Goldkette unit consisted of:

- Fred “Fuzzy” Farrar (trumpet);

- Bix Beiderbecke (cornet);

- Sonny Lee (trombone);

- Stanley “Doc” Ryker, Charles “Pee Wee” Russell, Frank Trumbauer (reeds);

- Irving “Itzy” Riskin (piano);

- Frank DiPrima (banjo);

- Dan Gaebe (bass);

- Dee Orr (drums).

The orchestra played at the Blue Lantern, a large ballroom known as the Casino before and after the Goldkette engagement. The musicians had living quarters in cottages at the lake. The married couples lived in nice cottages, the single guys, in particular, Bix, Don, Itzy, and Pee Wee lived in a rather dilapidated cottage. The state of disorder of the cottage where Bix stayed was legendary. Norma Ryker tells about this in her diary published elsewhere on this site. An amusing story, told by Martin Skiles, is related in p. 211 of Bix, The Leon Bix Beiderbecke Story by Philip and Linda Evans.

“Bix was living with other musicians in this cottage, during the summer.

A visitor, who was astonished at the extremely unkempt cottage (half-filled food cans, dirty laundry, etc., weeks old.) asked the question:

What do you do with your garbage?

Bix replied:

We just kick it around until it disappears.

A few days ago, Rich Johnson of the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Society informed me that the cottage was for sale for $40,000. The owners live in LaPorte, Indiana. Rich writes on 8/12/00: “The owner did not know that Bix was connected with the house until Fred Turner (the writer of the article about Bix in the Smithsonian issue of July 1997) showed up a week or so ago. In fact, she had never heard of Bix until then. She told me the original house was 27 feet wide by 18 feet deep. A kitchen and bath have been added since. Her son is asking $40,000 for the house alone or with the property which is 60 feet by 100 feet. The house is about 2 to 3 blocks from the lake. Since the Fred Turner visit, the owner has gotten interested in Bix and has purchased the book, “The Leon Bix Beiderbecke Story” by Phil & Linda. I told her about the documentary so she ordered one from us. (Another Bix convert!)” Phil Pospychala first told Rich Johnson about the availability of the cottage and advised the Putnam Museum that it was for sale. Rich wonders if anyone has any ideas for saving it.

I thank Rich Johnson for the information he provided and for giving me permission to include a portion of his message in the above account.

“Bix Lives”, The Worshippers of Bix, The Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Band, and The Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Society.

It is well known that the motto of the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Society is “Bix Lives”. These two significant words are included in their logo and also are prominently displayed on large banners during the annual Bix Festival.

The first documented mention of the motto that I could find in print is in the liners for the 1952 Columbia album GL-507 (reissued in the 1960s as Columbia CL-844), “The Bix Beiderbecke Story, Volume I, Bix and His Gang”. The liners read in part:

Bix collectors are really avid about their boy. There’s one in the middle west who rubber stamps all his letters BIX LIVES.

So wrote the jazz historian and record producer George Avakian. According to Thomas Selleck (e-mail message 2/20/99), the administrator of the “Bix Lives Jazz Award”, the avid Bix collector who stamped his letters with the motto BIX LIVES was his father, Lincoln Selleck (Thomas still has Lincoln’s “Bix Lives” stamp). It turns out that Lincoln had been pressing George Avakian to re-issue Bix’s recordings. Clearly Lincoln must have made an impression on Avakian. If not, why would he refer to the “Bix Lives” fan in the liners for the Columbia reissues of Bix’s recordings? As a youngster in the mid-40s, growing up in Nichols, Connecticut (not the Midwest), Lincoln Selleck discovered Bix’s music and became enchanted with it. In the photograph on the left Lincoln is holding the 1947 Columbia four-78 rpm album C-29 “Hot Jazz Classics, Jazz As It Should Be Played by Bix Beiderbecke” (the liners for this album were written by George Avakian also).

Beginning in the early 40’s, Lincoln and his grade school buddies Dick Hadlock and Howard Linley spent interminable hours listening to any Bix record that they could get their hands on. Dick Hadlock is a musician and writer; he currently plays clarinet and soprano sax with the “San Francisco Feetwarmers” and has a radio program, “Annals of Jazz”, every Sunday from 7 to 8 pm Pacific Time on KCSM, Jazz 91, a radio station in San Mateo, CA. Howard Linley is a jazz musician who currently plays with the PK4 Quartet in Connecticut.

The years of total devotion to Bix’s music on the part of these youngsters culminated in ca. 1947 with the founding of the W.O.B. (Worshippers of Bix) club. According to Thomas Selleck (e-mail messages of 2/17/99 and 6/8/99):

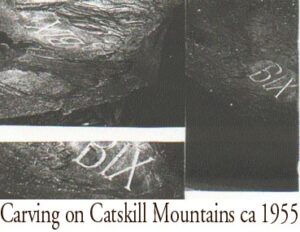

Yes, the W.O.B. still exists — two of the founding members (and the only two directors) are still playing jazz — and still accepting applicants. It is a pretty exclusive club that has never been really publicized — only a handful of real Bix devotees even know about it — and the perks are simply a membership card and the knowledge that you are among an elite group of Bix fans. No meetings, no newsletters. It was founded in around 1945 by Dick Hadlock and Howard Linley and my father in Nichols CT — my father carried WOB membership card #1 in his wallet until his untimely death in 1994. W.O.B. was/is a very informal and partially tongue-in-cheek club and Dick is not eager to publicize it. The WOB was always an undercover type of association. Dick printed up 100 WOB cards (of which many remain) but it was never intended as a serious organization. Jimmy McPartland and Jim Gordon are among the handful of cardholders. Dick is still open to awarding WOB cards to the worthy with the caveat that applicants must expect to struggle to prove that they deserve the honor — and then cheerfully accept the totally subjective judgment of Hadlock and Linley as to whether they qualify. To date (since 1945) there are only 20 or so members.” Member #9 is Thornton Hagert who won his card by carving the word Bix in Roman style on a flat edge on top of a mountain in Fleischman, New York.

Thomas Selleck continues:

In addition to the Columbia Bix and His Gang re-issues, Link’s early exposure to Bix came in the form of obscure acetate 78 rpm recordings from Boris Rose (Boris Rose was a record collector in NYC who made acetate recordings of many obscure out of print jazz 78s and sold them. Lincoln bought a lot of them and shared them with Dick and Howard), which were played for the members of the W.O.B. Club.

Howard Linley recalls:

We had never heard anyone like Bix before. We almost wore out those records – I remember playing the bizarre novelty tune “Felix the Cat” over and over again! We all thought Bix was great, but Link was the most hard-core of us all. He even used to write “Bix Lives” with the lawnmower across his mother’s front lawn!

Link’s red-ink “Bix Lives” rubber stamp graced his many missives to George Avakian whom he lobbied incessantly during the 1940s to re-issue Bix’s recordings. During his life Lincoln Selleck inspired many young people (and many older people, too!) to savor the special music of Bix Beiderbecke and his contemporaries”.Dick Hadlock used to write “Bix Lives” in many places, including the walls of the army barracks and of the Commodore Music Shop on 42nd Street, New York City.

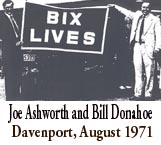

The next appearance of the “Bix Lives” motto that I can document is related to Bill Donahoe and his annual Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Stomps. Always prominently displayed were banners proclaiming “Bix Lives”. Bill Donahoe and the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Band of New Jersey brought the “Bix Lives” tradition with them during their 1971 trip to Davenport to play at Bix’s graveside. As recounted by Jerry Verbel (March 1998 issue of the Jersey Jazz Magazine, p. 16), “As we disembarked, Joe Ashworth (C melody sax) of Jacksonville, Florida’s Jacksonville All Stars, slapped a red-and-white bumper sticker above the cabin door letting the soon-to-board passengers know “Bix Lives!”. The band displayed banners asserting “Bix Lives”.

Today, the motto is found everywhere in Davenport during the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Festival.

Helpful contributions from Thornton Hagert and Howard Linley are gratefully acknowledged. I am profoundly grateful to Thomas Selleck, Dick Hadlock, and Bill Donahoe. Without their help, this section could not have been written. The images of the carving of Bix by Thornton Hagert and of Lincoln Selleck mowing the lawn are through the courtesy of Dick Hadlock. The photograph of Lincoln holding Bix’s record is courtesy of the Lincoln C. Selleck “Bix Lives” Jazz Award Competition Copyright C 1999. The image of Joe Ashworth and Bill Donahoe holding the “Bix Lives banner” was kindly provided by Bill Donahoe.

The Sweet and Hot Music Foundation Walk of Fame

In the May 2002 issue of “Jazz Me News,” Don Mospick writes:

The Sweet and Hot Foundation has dedicated a series of beautiful commemorative plaques that are permanently embedded in the concrete around the poolside area of the L.A. Marriott Airport Hotel. The tradition, launched during the first Sweet and Hot Music Festival in 1996, was established to acknowledge the work of musicians and composers who have contributed to America’s Golden Age of popular music.

The inductees in 1996 were Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, George Gershwin, and Benny Goodman. In 1997, the jazz musicians honored with a bronze plaque in the “Sweet and Hot Music Foundation Walk of Fame” were Bix Beiderbecke, Ella Fitzgerald, Cole Porter, and Thomas “Fats” Waller.” For a complete list of inductees, go to http://www.sweethot.org/walk.html To see what was written about Bix when he was inducted, go to http://www.sweethot.org/bix.html I am indebted to Wally Holmes, director of the Sweet and Hot Music Festival, for permission to post the images, to Don Dade for kindly sending the scans, and to Gordon for his overall help.

The Bix Obituary in the Melody Maker

The Melody Maker issue of September 1931 carried an obituary about Bix. Enrico Borsetti scanned the page from the magazine and kindly sent to me for uploading it here. Scroll down until you see the article. Note that an incorrect date -August 7, 1931- is given. The correct date is August 6, 1931.

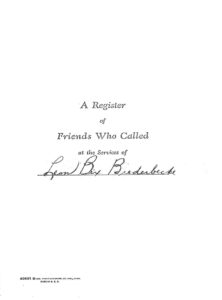

A New Glance At Bix’s Funeral

Information about Bix’s funeral in Davenport is available, so far, in the two key books about our musician: “Bix, Man & Legend” by Richard M. Sudhalter and Philip Evans and “The Leon Bix Beiderbecke Story” by Philip Evans and Linda Evans.

“Bix, Man & Legend” by Richard M. Sudhalter and Philip Evans

The first book informs us that:

Bix was buried the following Tuesday [August 11, 1931] after the largest funeral in the city’s memory. Radio station WOC devoted the day to Bix’s records (..). But not a single jazz musician or friend of Bix’s walked among the men who carried the coffin down the gravel drive in brilliant Iowa sunshine.

Waid Rohlf (pages 334-335):

There was only one musician – from a wealthy family – in the lot. He was a longhair violinist and orchestra conductor named Bill Henigbaum. The rest of the pallbearers were wealthy friends of the family, some of society’s upper crust. They were either selected by C.B. [Burnie] or by Bix’s folks

The names of five pallbearers are given on page 399: George Von Maur, Louis Best, Karl Vollmer Jr., William Henigbaum Jr., and Dr. John Wormley.

“The Leon Bix Beiderbecke Story” by Philip Evans and Linda Evans

Published 25 years later, the second book is much less “lyrical” and it reads :

Aug. 9 (Sun) – Bix’s body arrived by train in Davenport at 10:30 p.m. His remains were taken to Hill & Fredericks mortuary (Brady at 13th), where he lay in state.

Aug 11 (Tue) – Services were held this morning at 11 o’clock at the Hill & Fredericks chapel with the Rev. Leroy Coffman of the First Presbyterian Church officiating. Private burial services were held at the grave in Oakdale Cemetery.

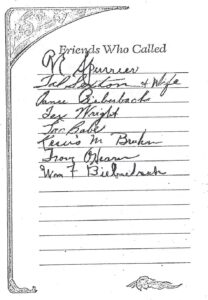

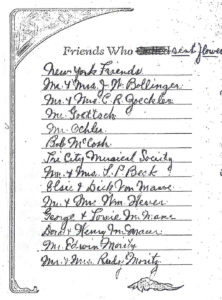

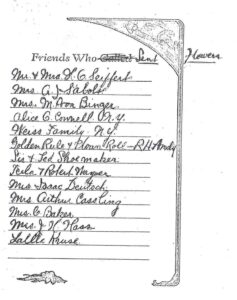

The names of six pallbearers are given: the above five ones and Richard Von Maur. (page 549). Page 550 gives the names of “Friends Who Called”: a limited list of nine persons. One of us (JPL) wanted to know more about this ceremony, and the first question was:

Who were these people calling and attending?

When asking about Bix and Davenport, the best door to knock on is, of course, Rich Johnson’s. What we found out follows:

“Friends Who Called”: these are the people visiting the Hill & Fredericks mortuary on August 9-11, and signing the register. They were incredibly few visitors: nine persons in total (of course, some may have come without writing their names down, but they can’t be many), which is nothing when one thinks of the number of musicians Bix had been playing with in this area, and all the people he knew in the city. We could identify all but one visitors’ names. They are as folows:

- Esten Spurrier, well-known Bix’s friend and story-teller;

- Tal Sexton and wife. He was a musician, living in Rock Island, IL, and he was the trombone player with the Carlisle Evans band in Davenport in 1921 (his picture is on page 50 of “Bix, Man & Legend”);

- Ernie Bieberback = Ernest A. Bieberbach. He died in 1969 in Davenport, age 66, and was a “Mississippi riverboat trombonist. He and his brother Bill played with such riverboat bands as Minnie Fitzgerald and her Tropical Jazz Band, and the Burke-Leins Novelty Orchestra on the excursion steamer Capitol.”

- Tex Wright. He is probably Foster H. Wright, also a musician living in Rock Island;

- ? “Babe”. Unidentified person.

- Lewis M. Bruhn = Louis Bruhn, a pianist with the Jimmy Hicks orchestra in December 1929,

- Trave O’Hearn. Well-known local band leader; Bix played with his orchestra in Davenport in December 1929.

- William T. Bieberback. Ernest’s brother (see above); “Bill Bieberbach, a professional trumpet player, who was often host to Bix Beiderbecke, died in 1965.”

All these visitors were musicians and Bix’s personal friends, even if only in limited numbers. Pallbearers on August 11. There were six.

- Louis Best. VP of Robert Krause Co., a garments store, located at 113-115 W. 2nd Street in Davenport, next to the Beiderbecke & Miller Wholesale Grocers (Bix’s grandfather’s store);

- George Von Maur. Sec. Treasurer for Henry Von Maur, Inc.; George Von Maur is featured among the persons interviewed by Jim Arpy for his Quad-City Times’ article, “People who knew Bix”. He was older than Bix, and his parents knew Bix’s folks.

- Richard Von Maur: Treasurer for the JHC Petersen Co., a big department store in Davenport’s 2nd Street, located next to Robert Krause Co. Bix’s brother, Charles ‘Burnie’, was at time in charge of its music department. Petersen-Von Maur still owns major stores in Davenport today.

- Karl Vollmer. VP of Motor Service Inc., his father was a doctor. Bix refers to him in a letter to his mother, dated May 7, 1920, where he wrote: Tonight I’m taking Vera L.C. to the R.I. Class play with Karlie Vollmer

- William K. Henigbaum. Treasurer of Iowa Furniture / Huebotter Furniture Co. He was born in 1897 (died in 1979) and a close friend of ‘Burnie’ and his wife Mary. His son, William Henigbaum, born in 1921, is the “longhair violinist” mentioned in “Bix, Man & Legend”. He did not attend the funeral and lives today in North Carolina, where he still teaches violin students.

- Dr. John Wormley. He was a prominent Davenport dentist and was in his late 40’s at that time. He was probably a friend of Bix’s parents.

These pallbearers were definitely belonging to the Davenport “upper class”, all members of the selected Outing Club (where the wedding of Bix’s sister had taken place in 1924).

Les Swanson is today 97. He remembers quite well the ceremony at the Hill & Fredericks’ chapel:

Some fifty to sixty persons attended the service, almost exclusively men.

Les was surprised not to meet with any other musicians, as he expected Esten Spurrier, at least, to be there… and he was not. Les stayed by himself, at the rear of the chapel, and left after the ceremony, speaking to no one. Burial services at the cemetery were private and limited to family members. The local radio station did pay a short tribute to Bix: during a dance broadcast, a text was read and pianist Bert Sloan played “In A Mist”. And that was it! It was hardly “the largest funeral in the city’s memory”…!

Searching for these elements, Rich Johnson was able to unearth new information related to Bix:

- The Petersen family was linked to the Beiderbecke family. Albert Petersen, ‘Uncle Olie’, was Agatha’s cousin’s husband. He was conductor of the Davenport brass band and gave Bix his first cornet lessons. Albert’s son, Ceno, had a pharmacy called Moetzel’s Drug Store, at 1511 Harrison Street, where Bix used to work, making some pocket money preparing ice cream sodas while he was attending Davenport High School;

- Joe Stroehle used to meet Bix at the pharmacy and go with him to the YMCA to play piano. Although I could play and had taken lessons – remembered Joe: Bix taught me many things on the piano that I would never have learned. He showed me how to play the 9th, 11th, and 13th chords which were unheard of back then. Bix was so innovative!

Here’s a copy of Bix’s funeral booklet:

I thank Steve Hester for his generosity in providing the images. Guest contributions by Jean Pierre Lion and Rich Johnson

A Letter From Bix to Nick LaRocca

The following letter was written by Bix Beiderbecke on Monday, 22nd Nov. 1922, on the train from Chicago to Davenport. It is addressed to Mr. D. Jas LaRocca, 225 West 11th St., New York City, N.Y. We have included a transcript of the text on the next two pages, including the post-script which we were unable to reproduce in its entirety. From Storyville No. 9 (Feb-March 1967) pages 29-31. Also transcribed in Evans and Evans, Bix: The Leon Bix Beiderbecke Story, p. 122.

Dear Nick,

Am on my way home from Chi that I’d take the opportunity to write you the dope. I saw Mike Fritzel last night and he seemed impressed when I told him about you boys wanting to come to Chi and that you would consider the Friars Inn if everything – “Do” and hours were satisfactory – I sure poured it on thick. Well, Nick Mike wanted to know the dope in regard to the money you boys wanted etc. and I said that you would write him the full particulars that I just didn’t know. All I knew was that you were the best lead in the country. Well he expects a letter from you, Nick. I’m sending your address to him so he can wire you – I was supposed to meet him today at 3’clock I left early so I left your address addressed to him at Friars. You write him about what combination you’ll have and everything else. I told him that you just made a record which pleased him – His address is Mike Fritzel, Friars Inn. Chi. Well Nick I wish you the best of luck – give the boys my best and tell that clarinet player to expect some “do” right soon & also tell him he’s the best boy I’ve ever met.

Sincerely,

B. Beiderbecke.

Rapollo & the band are moving in about a week they aren’t going to New York for a while – it ap.

Also send you Eddie & Tony his regards. I am grateful to Fredrik Tersmeden for sending me a copy of the letter.

The Solos of Bix – Keys

–Eb–

- Sensation

- Big Boy

- I Didn’t Know

- Davenport Blues

- Singin’ the Blues

- Slow River

- Humpty Dumpty

- Jazz Me Blues

- Clorinda

- Sorry

- Cryin’ All Day

- A Good Man Is Hard To Find

- Changes

- Mississippi Mud

- Show Boat

- When

- Lila

- Somebody Stole My Gal

- Forget Me Not

- You Took Advantage Of Me

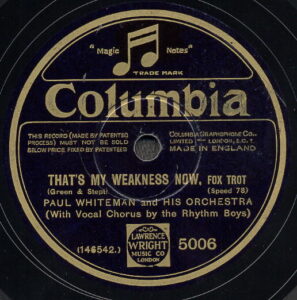

- That’s My Weakness Now

- Out of Town Gal

- Bless You Sister

- Ol’ Man River

- Wa-Da-Da

- Gypsy

- Margie

- High Up On a Hill Top

- Raisin’ the Roof

- I Like That

- Oh! Miss Hannah

–Ab —

- Tiger Rag

- Proud of a Baby Like You

- Hoosier Sweetheart

- Ostrich Walk

- Riverboat Shuffle (2)

- Three Blind Mice (1)

- Clementine

- There Ain’t No Land

- Just an Hour of Love

- Three Blind Mice (2)

- Lonely Melody

- Back in Your Own Backyard

- Dardanella

- Borneo

- Louisiana

- Because My Baby Don’t Mean Maybe Now

- Sweet Sue

- Sentimental Baby

- No One Can Take Your Place

- Barnacle Bill the Sailor

–F–

- Jazz Me Blues (1)

- Oh Baby

- Riverboat Shuffle (1)

- Idolizing

- Clarinet Marmalade

- I’m Coming Virginia

- Baltimore

- There Ain’t No Sweet Man

- Love Nest, The (1)

- Love Nest, The (2)

- Baby Won’t You Please Come Home

- Futuristic Rhythm

- Reaching For Someone

- China Boy

- Deep Harlem

- I Don’t Mind Walking In the Rain

- I’ll Be a Friend with Pleasure

–Bb —

- Copenhagen

- I Need Some Pettin’

- Royal Garden Blues (1)

- Royal Garden Blues (2)

- Since My Best Gal Turned Me Down

- There’ll Come a Time

- From Monday On

- Strut Miss Lizzie

–C —

- Tia Juana

- Krazy Kat

- There’s a Cradle in Caroline

- Mary

- Lovable

- Felix the Cat

- Tain’t So Honey

- ‘Tain’t So Deep Down South

–G —

- Way Down Yonder In New Orleans

- Sugar

- Our Bungalow Of Dreams

- Love Affairs

- Loved One

–Db —

- Goose Pimples

–D —

- Waiting At the End Of the Road

Guest Contribution by Paul Bocciolone Strandberg.

Summary

The solos of Bix are played in the following keys:

- Eb: 31

- Ab: 20

- F: 17

- Bb: 8

- C: 8

- G: 5

- Db: 1

- D: 1

I did not count alternate takes or re-recordings of the same arrangement (From Monday On). Of course, what a solo is not scientifically defined in this context. I consider the first chorus of “Ol’ Man River” as a solo for Bix, as well as the verse on “A Good Man Is Hard To Find”. On the other hand, I don’t count his ad-lib playing on “I’m Looking Over A Four-Leaf Clover” or “In My Merry Oldsmobile” as solos.

The reason that some keys are more comfortable than others depends on the tuning of the instrument. Since most musicians use Bb-tuned instruments -such as trumpet, clarinet, and tenor sax- the five most common keys in jazz are Bb, Eb, F, Ab, and C. The oddest in the above list is the solo in D natural on “Waiting at the End of the Road”. Neither Bix nor his colleagues were limited to play in certain keys. In Bix’s case, he got good training to improvise and formulate his musical ideas in any key from playing along with records.

By adjusting the speed he could practice his cornet in the new keys that resulted from this. It is said in the Sudhalter-Evans biography that he preferred the key of Eb on the cornet but this he had in common with many others and many popular melodies as well as military and classical music fit with the cornet in this key. The choice of key normally depends on the range of the instrument and the range of the song that is going to be played; but when it comes to improvising freely, the facility of fingering and the response of the instrument on certain notes may have big importance for the performer.

In most cases, Bix had no influence over the choice of key when a stock arrangement was recorded and when he only had a short solo to play in a big band arrangement. In many cases the key of a tune is fixed as when you play standard tunes like Royal Garden Blues (solo in Bb), China Boy (F), and Tiger Rag (Ab) We can note some examples when he changed keys from the common ones. “Jazz Me Blues” was changed from F as with The Wolverines to Eb when he was in charge of his own “gang”. From ODJB he changed the key of Margie from F to Eb also. The early recording of “Riverboat Shuffle” was in F while the one he made with Trumbauer contained a solo in Ab. In some tunes the intentions of the composer are respected; this results in performing in less common keys, as for example “Way Down Yonder In New Orleans” (G) or “Goose Pimples” (Db). This shows that Bix and his session mates did not change key to facilitate matters, which has often been the case in latter-day performances of the original jazz. (About Bix’s piano playing it is said that he preferred to play everything in C, but from there he would make excursions anywhere and use all kinds of colorings. He probably did not often do a full performance in public on the piano and thus did not need to use different keys for variation.) Guest Contribution by Paul Bocciolone Strandberg

Guest Contribution by Paul Bocciolone Strandberg. I am grateful to Paul for choosing to publish his analysis of the keys of Bix’s solos in the Bixogrphy. February 4, 2003.

Bismark Herman Beiderbecke on Bix’s Music

The accepted dogma in Bixology is that Bix had poor relations with his father. I do not agree, but that is a question that I will address in the future, not in the present post. What is clear is that Evans and Evans provide no information about what Herman had to say about Bix’s music and his life. There is one exception that I can remember. It has to do with the time when Marty Bloom hired Bix to play with the Orpheum Time Band Revue. According to Bloom (E & E, p. 110-111), around May 24, 1922, the band was rehearsing when Bix’s father appeared. Following a conversation between Bix and his father, Bix told Bloom, “I’m sorry to do this to you, but I’ve got to go back to Davenport, today with my father.” There are a couple of letters from Bix to his father, but I can’t think of an account of Bismark talking about Bix’s music.

The February 16, 1938 issue of “The New Republic” included an article -Swing Music- by Charles Edward Smith. In the article, Smith discusses the origins of jazz. As he mentions various musicians, Smith writes the following about Bix:

He had proved a natural genius to start with, having an unerring tonal and rhythmic sense. And so, about the time King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band was sending them to a Chicago drink and dance place, this young man was setting up to capture the world as the ad-libbing genius of the Original Wolverines. He arrived on the big time with Jean Goldkette’s sensational band, and when that broke up went to Whiteman. Contrary to popular opinion, he could read and write music, but -since he improvised and since Whiteman by his own statement was aware that Bix could get more music into three notes than all the rest of the band in a full chorus- he was given blank spaces to play while with the Whiteman orchestra.

When Bix came home, his father reported afterward, he would talk so much about his admiration for the work of such other musicians as Red Nichols and Hoagy Carmichael that the folks never realized his own superlative qualities and fame.

The statement attributed to Bix’s father is very significant. It shows, for the first time I believe, that Bix’s father knew some names of jazz musicians and talked about Bix and his fellow musicians to someone, jazz historians perhaps? One of the names is not surprising at all, that of Hoagy. We know of the long and close friendship of Hoagy and Bix. Red Nichols’ name may be surprising to some, especially since there are accounts of Bix making negative comments about Red’s musicianship. However, it is clear that Bix and Red were good friends. They met in 1924, they roomed and drank together in subsequent years, and one of the last phone calls -if not the last- that Bix made in his much too short life was to Red Nichols.

Finally, it is relevant, in the context of the recent thread about Bix’s reading skills, what Smith has to say on the subject. Unfortunately, Smith simply makes the assertion about Bix being able to read and write music but provides no references.

When Did Bix Become Bix?

University of Iowa Record of Bix Enrollment

Bix enrolled at the University of Iowa in the Spring Semester 1925. His tenure in school did not last long: just 18 days, from February 2 to February 20, 1925. What follows is the only extant document in the archives of the University of Iowa.

The document is practically illegible. Here is the information of interest.

Enrolled as Leon Bix Beiderbecke for the Academic year 1924-1925.

Date of Matriculation in University: January 1925.

Date of birth: March 10, 1904.

Institutions Previously Attended: Davenport, Ia. H.S. 3 years

Subjects:

- Phil. (logic & ethics) 2: 4 hours

- Engl. (rhet.) 02: 3 hours

- Music (intro. to) 02: 3 hours

- Music (mod. comp.) 116: 2 hours

- Music (rom. comp.) 114: 2 hours

The two handwritten notations read as follows:

Not permitted to continue 2-20-25 Indefinitely suspended and not permitted to re-register until officially restored to good standing 2-24-25

A few comments:

- Note that Bix gives his year of birth as 1904. Error on Bix’s part or on the part of the person who typed the form? Done by Bix on Purpose?

- Bix gives only the Davenport High School as “Institutions Previously Attended.” Bix fails to mention his year in Lake Forest Academy. Oversight? Concealed on purpose?

- The course schedule is slightly different from the one given by Evans and Evans.

A Myth A Myth A Myth.

A Myth Demolished: The Photo of Bix Purportedly Taken in Davenport in 1921 was taken in 1924

A few years ago, Frederick C. Wiebel, Jr., sent me a provocative message. Fred wrote, “The famous photo you have posted on the top of your website is not the 1921 photo taken in Davenport with Fritz Putzier. That photo is lost, if it ever existed. What you display is a photo from the Wolverine photo sessions. An individual shot of Bix.”

Let’s go back a couple of years to the Tribute to Bix of 1999 in Libertyville. On the Saturday of the meeting, Phil Pospychala showed a large photo of Bix found in a flea market in Florida. Some people thought that the photo could be an alternate pose of the photo taken in Davenport in 1921. I had seen that photo on the inside cover of Klaus Scheuer’s “Bix Beiderbecke: Sein Leben, Sein Musik, Sein Schallplatten.” The photo was not a portrait of Bix. It was a close-up enlargement of Bix from a photo with the Wolverines taken in Cincinnati in 1924. To see the photo of the Wolverines, go to:

You will see Bix in the center and slightly to the right of the photo, in a pose very similar to the alleged 1921 photo. I left Libertyville early on Sunday, and, as soon as arrived home, I sent Phil a fax with the photo of Bix from Scheuer’s book and the explanation that the Wolverines photo was cropped and enlarged to look like a portrait of Bix. I assumed that the similarity between what I thought was the 1921 photo and the photo of Bix enlarged from the Wolverine photo was due to Bix’s propensity to sit in a certain way and to hold his cornet in his right hand and resting on his right leg. However, Fred’s message convinced me that what we know as the 1921 Davenport photo was, in fact, taken in 1924 in Cincinnati, probably within minutes of the photo of the Wolverine orchestra.

To see the so-called 1921 photo side by side with the enlargement of the cropped photo of the Wolverines:

For a different view go to:

Fred provides the following analysis of the two photos. “Here are the two Bix photos in question side by side at about the same size. Even with the different printing processes, they are almost identical. The left photo is a solo so Bix is more engaging with the camera. The body language is very similar as he’s spread out a little and turned somewhat to his left. In the right-hand shot, he’s a little crowded, pulled in his leg, has unbuttoned his coat, put his fingers around the valves, and clenched his other hand. The cuffs have the same cut and flair. The hankie is almost the same shape. The tie is crooked in both and has the exact same wrinkles. The collar over the tie is the same in each photo and the way the tie is exposed around the neck. The jacket sleeves are way too long and bunched up and wrinkled in the same exact folds. It’s more apparent in the stand-up shot holding the banner. The vest is forcing up the shirt in the same manner with identical central white lines. The way the hornbell sits on his knee is in the exact same position. The wrinkles in his crotch and the way the light hits them are the same. For these two photos to have been taken three years apart is hard for me to believe.”

I think Fred’s analysis and comparison of the two photos provide a compelling argument for the inference that they were taken on the same day, minutes apart. Since, we know the date of the Wolverine photo (1924, in Cincinnati, ), the inescapable conclusion is that the famous photo of Bix was also taken in 1924.

There is some supporting evidence for this conclusion. In his book “The Stardust Road”, Hoagy Carmichael includes, between pages 122 and 123, the famous photo of Bix with his cornet. The caption reads, “Bix (Leon ) Beiderbecke. Photograph taken about 1924.” In his book “Twelve Lives in Jazz”, Duncan Schiedt provides a good quality copy and writes the caption, “The classic Beiderbecke portrait, probably taken in 1922, either in Davenport or (more probably) in Chicago.” In their book “A Pictorial History of Jazz”, Keepnews and Grauer write the following caption for the famous photo, “Leon ‘Bix’ Beiderbecke in 1923.

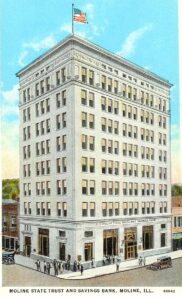

“Where does the myth come from? Fritz Putzier wrote to Phil Evans on 4/18/73, “Probably the most appropriate photo would be the one taken with Bix the day we had on our tuxedos, prior to going to Moline to play for the opening of the bank [August 30, 1921; ed.]. I wish I could remember what possessed us to do such a thing, neither of us was a show-off. I don’t remember any pending occasion that required the use of our pictures. Perhaps it was a youthful, enthusiastic whim and a feeling of importance, all dressed up in tuxedos. It prompted one of us, probably me, knowing Bix as I did, to suggest a picture.” (Evans and Evans; Bix: The Leon Beiderbecke Story, p.62). The account in Sudhalter and Evans’ “Bix: Man and Legend” goes as follows. ” Bix, meanwhile was keeping only too busy. Ralph Miedke hired him for the grand opening on Tuesday, August 30, of the Moline State Trust and Savings Bank. The band was scheduled to play from 1 to 6 P. M., and for the first time in his life, the younger Beiderbecke had to wear a tuxedo. “How do I look, Mother?’ he asked, turning in the bedroom mirror. Aggie, full of doubt over her son’s future, had nevertheless to admit that he cut a handsome figure. Bix took the stairs two at a time, stopping only to grab his cornet. ‘Where are you off to?’ his mother asked, puzzled. “It’s only nine in the morning, and you don’t have to play for another four hours.’ Bix laughed. ‘ Fritz [Putzier, ed.] and I are going to have our pictures taken in these li’l ol’ fancy suits.’ And out the door, he bounded. The photograph taken that August morning in 1921 has become the model by which Bix Beiderbecke is now recognized.” The photos of Fritz Spurrier and Bix are given on the page opposite the text, courtesy of Fritz Putzier. Clearly, the story comes for Fritz.

Two final points. Fred writes, “The lighting on the Putzier picture is totally different.” Indeed, they are. There are a few photos of Bix from 1921, and 1922. They can be found on pages 101-103, 106, 107, 113-115 of Evans and Evans. No photos are available in 1923. The 1922 photos are of poor quality. Nevertheless, I believe I can tell that Bix did not part his hair at that time.

All in all, it seems clear to me that the famous photo of Bix, generally accepted to have been taken in Davenport in 1921, was taken in 1924, probably in Chicago.

Here is a vintage postcard of the State Trust and Savings Bank, Moline IL.

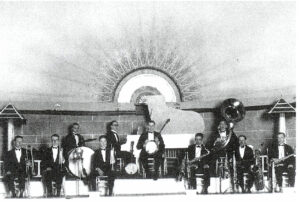

The following is a photo (without Bix) of the Ralph Miedke Society Orchestra.

I thank Frederick C. Wiebel, Jr. for the scan of the photos of Bix side by side, and Rich Johnson for the scans of the photos of the Moline Bank and of the Miedke band.

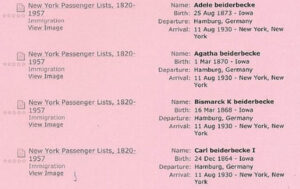

The Trips to Germany of Louise Beiderbecke and of Agatha and Bismark Beiderbecke.

Bix’s grandparents were Carl Beiderbecke (changed his first name to Charles) and Louisa Pieper (changed to Louise Piper). Charles was born in Westphalia, Prussia in 1836. and died in Davenport in 1901. Louise was born in Hamburg, Prussia in 1840 and died in 1922 in Davenport while Bix had an engagement in Syracuse. Charles and Louise came to America in 1853, but in different ships and at different times of the year.

Charles and Louise went to Davenport in 1856, but not at the same time. They met in Davenport and got married in 1860. They built their home at 532 W. 7th Street in 1880. Louise lived in the home she and Charles built until her death in 1922. Charles and Louise had four children: Carl Thomas, Ottilie, Bismark Herman, and Lutie. Bismark was Bix’s father.

Bix did not know either of his grandfathers but was quite close to Louise (oma). According to Leon “Skis” Wernetin, a high school classmate of Bix’s, “He and his grandma were great buddies. Her piano was one of the big attractions for Bix. When we’d go to the silent nickel movies, Bix didn’t care about the plot. He just wanted to hear the guy who played piano accompaniment. As soon as the show was over, he’d hurry back to his grandma’s to play on her piano what he’d just heard. He was just as crazy then as he was later, not afraid of anything. He was quite a character even as a kid. His grandma was quite a character, too, and a good piano player. She was always ready to have him play the piano and I guess she was quite proud of him. But we kids never realized he was that good.” [July 24, 1988 issue of the Quad-City Times].

Louise visited Germany in 1907. She was accompanied by her son Carl. They came back on the Grosser Kurfurst which arrived in New York on September 17, 1907. Both Louise and Carl are described as US citizens. Carl’s name is actually given as Charles. Here are the passenger records for Charles and Louise from the Ellis Island records:

First Name: Charles T.

Last Name: Beiderbecke

Ethnicity:

Last Place of Residence:

Date of Arrival: Sep 17, 1907

Age at Arrival: 42y

Gender: M

Marital Status:

Ship of Travel: Grosser Kurfurst

Port of Departure: Cherbourg, France

First Name: Louise

Last Name: Beiderbecke

Ethnicity:

Last Place of Residence:

Date of Arrival: Sep 17, 1907

Age at Arrival: 67y

Gender: F

Marital Status: M

Ship of Travel: Grosser Kurfurst

Port of Departure: Cherbourg, France

Manifest Line Number: 0003

According to http://www.historycentral.com/NAVY/Steamer/Aeolus.html, “The Grosser Kurfurst was a steel-hulled, twin-screw, passenger-and cargo steamship launched on 2 December 1899 at Danzig, Germany, by the shipbuilding firm of F. Schichau for the Norddeutscher Lloyd Line—made her maiden voyage to Asiatic and Australian ports before commencing regularly scheduled voyages from the spring of 1900 between Bremen, Germany, and New York City which continued until the summer of 1914.” Here is an image of the ship.

It makes sense that Louise wished to see her native country and relatives. She had come to the US as a 13-year-old girl. By 1907, she had been in the US for 54 years. Her husband had died six years earlier and she had an excellent financial situation. In 1907, Louise was 67 years old, and it makes sense that she would not want to undertake the long trip overseas by herself. Thus, her oldest son Carl Thomas accompanied her.

In 1930, Carl visited Germany again. This time he went with his wife Adele, his brother Bismark, and his sister-in-law Agatha. Here is the listing from Ancestry.com

Note the misspellings in Bismark’s first name and middle initial (should be H). Also, Carl’s middle initial is misspelled (should be T). One more minor point. Carl’s birth date is given as 24 Dec 1864. Evans and Evans give 24 Dec 1865. Here is the original manifest.

The two Beiderbecke brothers and their wives left Hamburg, Germany on the S.S. Cleveland and arrived in New York on 11 Aug 1930. We see that Bismark’s and Agatha’s destination was New York, whereas Carl’s and Adele’s destination was Boston. The S.S. Cleveland was one of the ships of the Hamburg America Line. Built in 1908, it made its maiden voyage Hamburg-Southampton-Cherbourg-New York on Mar 29, 1909.

Here is a postcard with an image of the S.S. Cleveland (http://www.cosmoclub.net/pc/pcimages/SS_Cleveland1.jpg)

When Bix’s parents arrived in New York, Bix was a member of the Camel Pleasure Hour Orchestra. Bix had been with the Camel Pleasure Hour since its premiere on June 4, 1930. It is not known when Bix’s parents left New York for Germany. Presumably sometime in July. It is highly likely that Bix’s parents visited his son on their way to Germany as well as on their return from Germany. There is corroborating evidence that indeed Bix’s parents visited Bix. According to Sudhalter and Evans, “Even Bismark and Agatha, encouraged at this turn of events, made the long journey east to visit their son during a broadcast in NBC’s studio B on Fifth Avenue. Bix, John Wiggin recalled, took special pride in introducing his parents to the friends on the show.” John Wiggin was the producer of the Camel Pleasure Hour. Bix’s parents’ visit during one of the broadcasts could have taken place either as they were on their way to Germany or on their way back, in July-August 1930.

I am grateful to German Bixophile Friedrich Hachenberg [Acknowledgment. I wish to thank Karl Gert zur heide.] for kindly and generously sending me all the information about Bix’s parents’ visit to Germany in 1930.

Bix In “Essential Jazz Records”

From “Essential Jazz Records, Vol. 1: Ragtime to Swing” by Max Harrison, Eric Thacker and Charles Fox, Mansell, 1999.

Review of the Wolverine Records

Review of the Bix and His Gang Records