Home > Biography

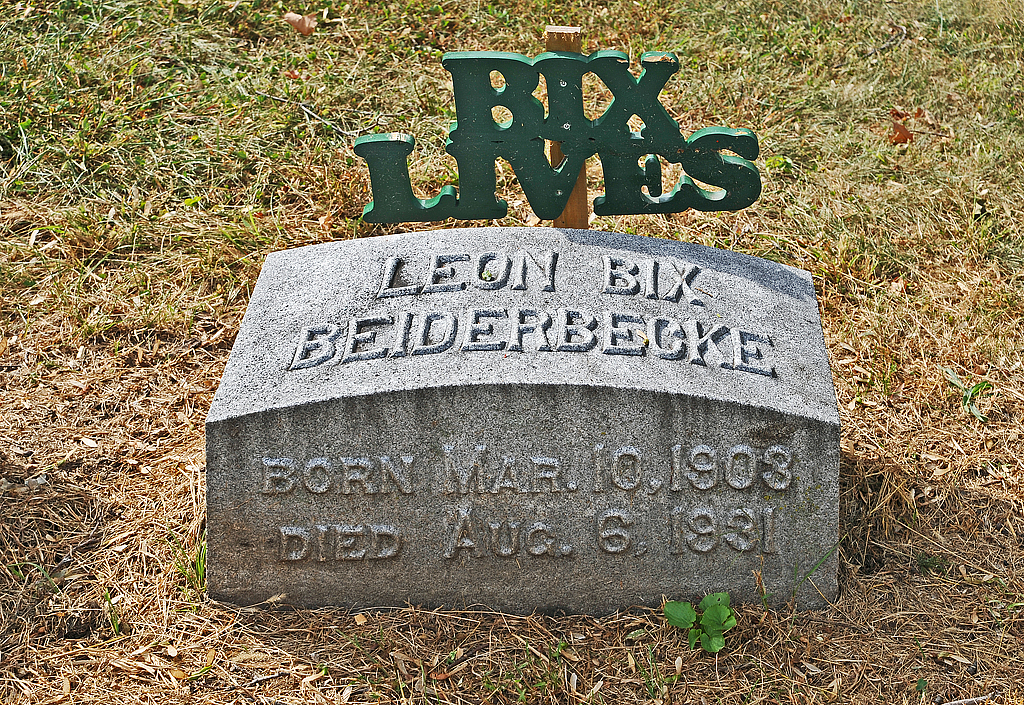

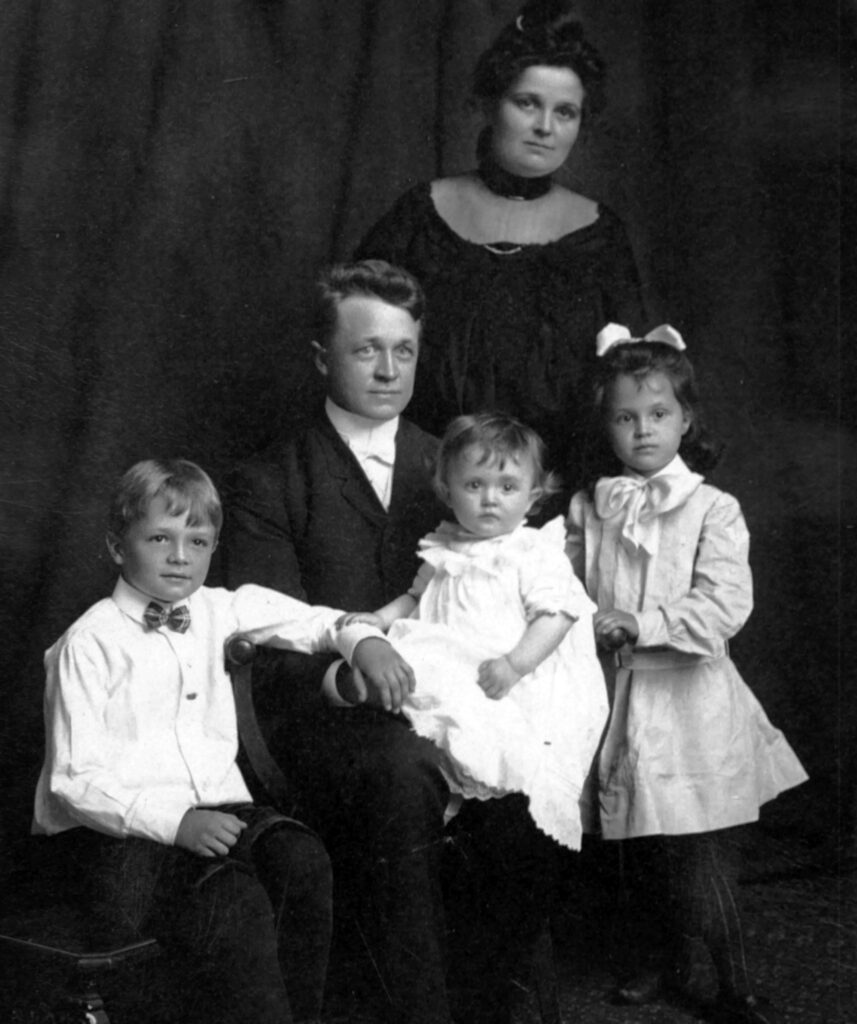

Leon Bix Beiderbecke was born in Davenport, Iowa on March 10, 1903. His father, Bismark Herman Beiderbecke, operated a successful fuel and lumber company. His mother, née Agatha Jane Hilton, was a gifted pianist. Bix was raised in a comfortable middle-class environment and learned to play the piano at an early age.

His musical ear was so amazing that he did not learn to read music: he would ask his music teacher to play a piece “to hear how it sounded”, and was able to repeat it note by note. In 1919, Bix’s brother, Charles (Burnie), purchased a Victrola which came with a few of the recordings of the Original Dixieland Jass Band. Bix was immediately taken by the music coming out of the horn. He listened carefully to the recording of “Tiger Rag” and reproduced what he heard at the piano.

Soon after, Bix turned to the cornet and taught himself how to play it. First, he played with a cornet that he borrowed from a neighbor. In September of 1919, Bix purchased his first cornet, a Conn Victor, and played in school events and with local groups. By the summer of 1921 he was fairly active and played locally with several bands, including his own Bix Beiderbecke Five.

In common with other amazingly gifted individuals, Bix’s academic performance in high school was inadequate. As a consequence, his parents decided to enroll him in Lake Forest Academy in Illinois, 35 miles northwest of Chicago.

Bix arrived in September of 1921 and soon after started playing with several bands, mostly in school functions, but occasionally sitting in with bands in Chicago. Bix’s escapades to Chicago after hours and poor grades contributed to his dismissal from the Academy in May 1922.

During the remaining part of 1922 and most of 1923, Bix divided his time between playing jazz at several locations in and around Chicago, a gig in Syracuse, and a conventional job in Davenport. In April 1923, the Benson Orchestra, including Frankie Trumbauer (generally known as Tram; he was a saxophone player), played in the Davenport Coliseum (known today as the “Col Ballroom”). This was an important occasion because Bix and Tram met for the first time.

By the end of 1923, Bix returned to Chicago, and his life as a professional musician began in earnest.

The Wolverine Orchestra was organized at the end of 1923 and had its heyday in 1924. Several dates in various locations in the Midwest, a phenomenal success at Indiana University, an appearance at the Cinderella Ballroom in New York City, and several historic recordings for the Gennett Recording Company marked a year of intensive activity.

Bix’s first recording was cut in February 1924 and released in May 1924. The record had “Fidgety Feet” on one side and “Jazz Me Blues” on the other. This recording was followed by several more. The legendary recordings of the Wolverine Orchestra became the basis of Bix’s growing reputation among jazz musicians.

In October 1924, Bix left the Wolverine Orchestra to join the Jean Goldkette Orchestra. Goldkette was a pianist and music entrepreneur with headquarters in Detroit, Michigan. His premier band was the Jean Goldkette Victor Recording Orchestra.

Bix’s first experience with the Goldkette group lasted less than two months and was rather frustrating. Unlike the situation with the Wolverine Orchestra where memorized arrangements were common, the Goldkette musicians were trained professionals and the ability to read scores was essential. Bix failed in this respect. This deficiency was compounded because of Goldkette’s contract with the Victor Company.

The recording director, Eddie King, had a distaste for hot jazz and apparently developed a strong dislike of Bix. Thus, by December of 1924, and to the disappointment of his fellow musicians in the band, Bix had to leave the Goldkette organization.

In January of 1925, Bix returned to Richmond, Indiana, and recorded, again for Gennett Records, his first composition, the immortal “Davenport Blues.” The record (flip side was Toddlin’ Blues) was issued under the name of Bix Beiderbecke and His Rhythm Jugglers and included:

He spent a couple of months in New York, where he stayed with Red Nichols, a cornet player who recorded prolifically in the 1920s and 30s, notable for his group the Five Pennies, and for his association with the great trombone player Miff Mole. Bix sat with the California Ramblers, which included the Dorsey brothers and the great bass saxophone player Adrian Rollini. He joined the Charlie Straight Orchestra in Chicago and stayed with that group until July. Bix then joined the Breeze Blowers in Island Lake, Michigan.

Some of the names in the band included musicians who, in the next few years, were going to play often with Bix in various bands: Bill Rank (trombone), Don Murray (reeds), Frankie Trumbauer (C-melody sax), and Steve Brown (string bass).

In August 1925, Bix joined the Trumbauer Orchestra in St. Louis and remained with the orchestra until May 1926, when both Bix and Tram joined the Jean Goldkette Orchestra. In September of 1926, Bill Challis joined the orchestra as arranger. Challis turns out to be a key figure in Bix’s life. His arrangements, both with the Goldkette and the Whiteman orchestras, provided plenty of room for Bix’s inventiveness and gift of improvisation.

The highlight of 1926 was a battle of the bands between the Jean Goldkette Orchestra and the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, in the Roseland Ballroom in New York City.

The Henderson band included such luminaries as Rex Stewart, Coleman Hawkins, and Buster Bailey.

The outcome of the battle was quite surprising. In the words of Rex Stewart (Jazz Masters of the Thirties, page 11) “This proved to be a most humiliating experience for us, since, after all, we were supposed to be the world’s greatest dance orchestra.” “The facts were that we simply could not compete with Jean Goldkette’s Victor Recording Orchestra. Their arrangements were too imaginative and their rhythm too strong.”

During the year 1927, the Jean Goldkette Orchestra had a busy schedule.

They played at the Graystone Ballroom in Detroit, traveled throughout the Midwest and the Northeast, recorded for the Victor Company, and made several radio broadcasts. This is also the year in which Bix reached the apex of his musical creativity. Small contingents of the larger Goldkette Orchestra, with the addition of some first-class musicians (such as the great bass saxophone player Adrian Rollini), led either by Frankie Trumbauer or by Bix produced a series of legendary recordings in 1927.

On February 4, Frankie Trumbauer and his Orchestra, with Bix (cornet), Jimmy Dorsey (clarinet), Bill Rank (trombone), Paul Mertz (piano), Eddie Lang (guitar), and Chauncey Morehouse (drums) recorded “Singin’ the Blues”. “Clarinet Marmalade”, another Bix classic, was on the flip side.

In May, Frankie Trumbauer and His Orchestra, including Bix, recorded four additional sides, including “Ostrich Walk”, “Way Down Yonder in New Orleans” and Hoagy Carmichael’s “Riverboat Shuffle”. The fourth recording, “I’m Coming Virginia”, is probably the most outstanding example of Bix’s profound lyrical improvisation.

In October, Bix Beiderbecke and His Gang (Bill Rank, Don Murray, Adrian Rollini, Frank Signorelli, and Chauncey Morehouse) recorded “At the Jazz Band Ball”, “Royal Garden Blues”, “Jazz Me Blues”, “Goose Pimples”, “Sorry”, and “Since My Best Girl Turned Me Down”. These recordings, together with those of Frankie Trumbauer and His Orchestra, exemplify some of Bix’s most creative work and represent a major component of his musical legacy.

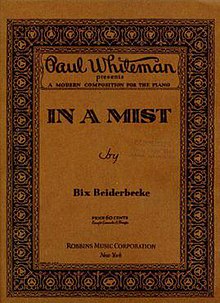

September 9, 1927, witnessed another milestone in Bix’s career. He recorded, for the Okeh Record Co., a piano solo of his composition, “In A Mist”. Undoubtedly, this is the best-known and most significant of Bix’s compositions.

A year later, on October 7, 1928, Bix played “In A Mist” as part of the concert presented by Paul Whiteman in Carnegie Hall.

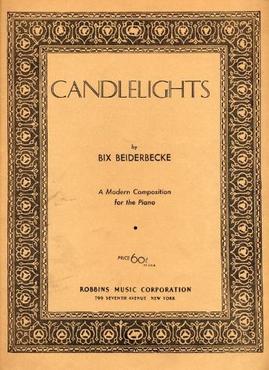

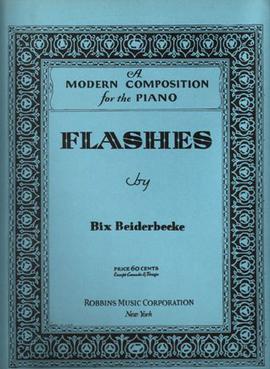

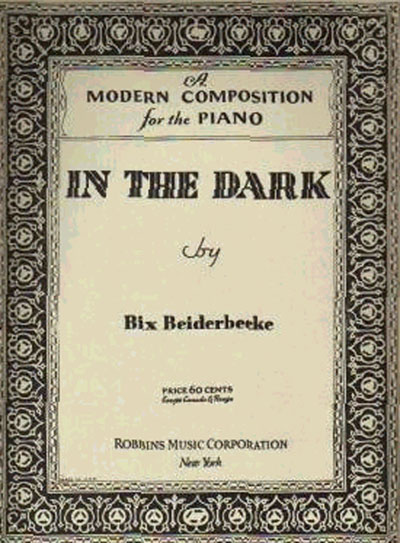

“In A Mist”, together with” Davenport Blues” and his other piano compositions, “Candlelights”, “Flashes”, and “In the Dark”, were published in 1938 by the Robbins Music Corporation of America as the creations of a “world-famed composer” and “The Foremost Exponent of Modern American Music”.

Subscribe and receive our latest updates in your inbox!

By the middle of 1927, the Goldkette organization was running a substantial deficit – the end of the orchestra was in sight. The last recording of the Jean Goldkette Orchestra, “Clementine”, took place on September 15 and turned out to be one of their best. Richard Sudhalter and Philip Evans in their book Bix: Man and Legend, p. 212, provide an insightful analysis of the recording:

By any standard, "Clementine" is an extraordinary record and a departure from all Goldkette performances before it. The band, lifted by (Eddie) Lang's guitar, sings along with a freshness and rich tonal balance rare on any recording of the 1920s and a rhythmic relaxation looking a good decade into the future. Bix fills in during the ensembles with the charm of a high-spirited schoolboy, and his solo, simple in construction, refashions a new tune out of the old with the same natural grace that turned "Singin' the Blues" into a piece of jazz history.

Richard Sudhalter, Philip Evans

When the Goldkette band dissolved, Bix joined Adrian Rollini and the New Yorkers, a group of highly talented jazz musicians which included, in addition to Bix and Rollini (bass sax), Sylvester Ahola (trumpet), Bobby Davis (reeds), Eddie Lang (guitar), Frank Trumbauer (C-melody sax), Chauncey Morehouse (drums), Don Murray (clarinet), Bill Rank (trombone), Frank Signorelli (piano) and Joe Venuti (violin).

We get a glimpse of white jazz at its best from recordings that the band made on September 28 and 30, 1927 under the Frankie Trumbauer name.

Although the choice of songs was not the most felicitous (“Humpty Dumpty”, “Krazy Kat”, “The Baltimore”, “Just an Hour of Love”, and “I’m Wondering Who”), we are treated to the musical inventiveness of a group of gifted and skillful jazz musicians doing outstanding ensemble work and playing highly imaginative solos.

Unfortunately, the New Yorkers lasted for only a few weeks and on October 27, Bix and Tram joined the Paul Whiteman Orchestra.

Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra had been playing in New York since 1920, and by the mid ’20s Whiteman was known (and imitated) around the world. In 1924, Whiteman commissioned George Gershwin to compose Rhapsody in Blue and performed it with his orchestra and the composer on piano at Aeolian Hall.

By the time Bix and Tram joined the Whiteman organization, Paul Whiteman was the King of Jazz.

The remaining of 1927 and all of 1928 represented a period of high activity for Bix, with engagements throughout the Midwest and the Northeast, parts of the South and the Southwest, recording dates of the full band, and recording dates of small groups led by Trumbauer or by Bix. Among the most notable recordings of 1928: “Changes”, “San”, “Mississippi Mud” (two versions, one by Whiteman and one by Tram), “There Ain’t No Sweet Man That’s Worth the Salt of My Tears”, “Dardanella”, “From Monday On”, “Somebody Stole My Gal”, “Louisiana”, “You Took Advantage of Me”, “That’s My Weakness Now”, “Concerto in F”, and “Sweet Sue”.

From the songs in this list, highlight “From Monday On”, one of my personal favorites. An excellent analysis of this recording is given by Stephen M. Stroff in his article Bix Beiderbecke: A 50th Anniversary Evaluation of a Legend (Classic Wax, August, 1981, page 9). “Yet the best examples of Beiderbecke’s improvising best are the three existing takes of “From Monday On” with Whiteman. Not only did Matty Malneck arrange two full choruses of Bix leading the brasses, but he also adapted one of Bix’s improvs to the string section – for the first and last time in a Whiteman recording – and gave him a 32-bar solo at the outset. The earliest take (3), with Jimmy Dorsey playing third trumpet and Steve Brown slappin’ the bass for all it’s worth, was the best (Dorsey and Brown were replaced two weeks later by Rank on trombone and Min Leibrook on tuba [bass sax, really]). Still, we must count ourselves lucky to have three takes of an extended Bix solo – for each is entirely different. Splicing the three solos together, in whatever order you choose (though -4, -6, -3 works the best), you will get 96 bars of uninterrupted Beiderbecke cornet, finding new paths in the song’s trite melody, bringing us closer to the Bix of legend.”

The years 1929 to 1931 were marked by a deterioration of Bix’s health. Years of excessive consumption of bootleg gin ravaged his young body. He spent a lot of time in hospitals and at home attempting to regain his health. But whatever progress Bix made while recovering, was quickly reversed – and more – when he returned to New York and resumed his unhealthy habits.

In spite of the erosion of his health, Bix still managed to participate in Whiteman’s Old Gold radio broadcasts and to produce some good recordings such as “China Boy” and “Oh, Miss Hannah”. The last recording of Bix with the Whiteman band (however, see the discussion in “Is It Bix or Not?”) in September of 1929, presciently entitled “Waiting at the End of the Road”, is worthy of special mention because of Bix’s subdued and moving solo anticipating what was to come. Bix had a couple of recording dates of consequence in 1930.

In May, he joined Hoagy Carmichael and other jazz giants – Benny Goodman, Gene Krupa, Joe Venuti, Eddie Lang, and Bud Freeman, among others – and recorded a couple of tunes. For eight months, since the session that had produced “Waiting at the End of the Road”, Bix had not made any recordings. Thus, it was important to know if Bix still “had it”. Indeed, he did, as witnessed in his solo in “Barnacle Bill, the Sailor,” which was nothing more than a novelty song.

As discussed by Edward J. Nichols in Jazzmen, edited by Frederic Ramsey, Jr. and Charles E. Smith:

"B. Freeman says Bix was very happy that afternoon and to hear his cornet on "Barnacle Bill" is to know that for at least one day Bix had it again the way he liked it. Thirty-two bars of his music stemming back to the greatest days and no doubt about it."

Edward J. Nichols

On September 8, 1930, Bix, under his name, put together a group that included some of the musicians who participated in the May date with Hoagy, and recorded three sides, one of which, “I’ll Be a Friend with Pleasure”, should be viewed as one of Bix’s best recordings. It is anticipatory of the swing era in its rhythmic construction and its orchestration. Bix’s solo, using a derby hat as a partial mute, must rank as one of his most melodic and poignant.

During the summer of 1931, Bix had occasional college dates, playing mostly with musicians who would become extremely successful in the mid-to-late thirties – Benny Goodman, the Dorsey brothers, Jack Teagarden, Artie Shaw, and Gene Krupa.

At the end of June, just weeks before his death in the summer of 1931, Leon “Bix” Beiderbecke wrote to his parents that he was planning to marry a young lady named Alice O’Connell, mother’s maiden name Weiss.

With the help of Alice, at the end of June, Bix moved from his usual address in New York City, the 44th Street Hotel, to apartment 1G of a new apartment building at 43-30 46th Street in Sunnyside, Queens.

By August, the end was in sight. Bix had had a cold throughout the summer and was extremely weak. Finally, Bix’s body could not cope with years of excessive drinking and little nourishment.

He died on August 6, 1931 at 9:30 P.M., and was buried in Oakdale Cemetery in Davenport, Iowa on August 11, 1931. By all accounts, Bix was a kind, gentle, and generous man. He was an individual of few words, introspective, and unconcerned by the superficial details and demands of daily routine. Music was the all-consuming focus of his life, the essence of his being; and in music, he wrought his everlasting legacy.