Information of Related Interest

A Book of Caricatures

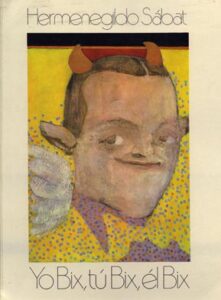

Yo Bix, tu Bix, el Bix by Hermenegildo Sabat, Editorial Airene, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1972. The title of the book translates as I Bix, You Bix, He Bix, of course, a tongue-in-cheek conjugation of the word

Bix as a verb, but perhaps more deeply, a subtle way of identifying I, You, and He with Bix. The book consists of 19 caricatures, 19 photographs of record labels from records by the Wolverine Orchestra, Bix and his Gang, the Frankie Trumbauer Orchestra, the Paul Whiteman Orchestra, and Hoagy Carmichael and his Orchestra, and a one-page introduction. The caricatures are excellent from a technical point of view, but somewhat surrealistic. This is clearly a labor of love. The author obviously adores Bix’s music and listens to it regularly. In fact, as he states in the introduction, “los necesito” means that he needs to listen to the recordings.

Riverwalk, Live from The Landing

This weekly radio program, produced by Pacifica Vista Productions and Jim Cullum for Texas Public Radio, is distributed by public radio stations. The programs focus on the music and lives of American Jazz Greats. The music is provided by the seven-piece Jim Cullum Jazz Band, now in its 35th year. As a 15-year-old lad in 1955, when he started playing the cornet, Jim Cullum was captivated by the sound of Bix’s recordings, and the choice of programs on Riverwalk reflects this interest. Thus, we find in the Riverwalk Jazz Master Show List the following items about Bix:

- Show #5, A Tribute to Bix Beiderbecke with guest artist Tom Pletcher.

- Show #20, Bix Lives! A Celebration of the Music of Bix Beiderbecke.

- Show #72, Bix & Hoagy: Midwestern Romantics of the Jazz Age.

- Show #96, Jazz Crazed: The Story of the Austin High Gang; the Early Music of Bix Beiderbecke, Benny Goodman, Hoagy Carmichael and Eddie Condon.

- Show #110, Bix and the Wolverines: Hot Jazz in the Midwest, recorded live at Stanford University in 1998.

Dances

According to the Library of Congress, reference numbers VXA 2923 (master copy) and VAE 0642 (viewing copy), on October 7, 1973, CBS-TV broadcast the program Camera Three entitled “The Bix Pieces“. This is a ballet choreographed by the dancer/choreographer Twyla Tharp to the music of Bix Beiderbecke. The program was produced and directed by Merrill Brockway and featured five dancers. Marian Hailey was the commentator. The video cassette is 28 minutes long.

Unfortunately, I have been unable to obtain, borrow, or view a videotape of the program. I would be grateful for a copy of a videotape of the program and/or any detailed information about its contents. The premiere of “The Bix Pieces” took place in Paris in November 1971 at the IX International Festival of Dance. Costumes: Kermit Love; Lighting: Jennifer Tipton; Music: Bix Beiderbecke, performed by Paul Whiteman’s Orchestra; “Abide with Me” by Thelonious Monk.

Twyla Tharp wrote an autobiography entitled “Push Comes to Shove”, Bantam Books, New York, 1992. She writes the following about how she developed “The Bix Pieces”.

Dancing continuously in the studio, I never stopped to mourn my father, but plunged daily back into working, where I could address his death without feeling I would break apart. Perhaps I felt that I could keep him with me in my dancing. I began to work on a piece to the music of trumpeter Bix Beiderbecke. Coming from the same period as Jelly Roll Morton, the Beiderbecke music was as light and airy as the other was rough-edged and earthy, as sophisticated in his arrangements as Morton was raw and close to the belt, as white as the other was black. Part One of “The Bix Pieces” was five songs – first me alone (twirling clear batons), then Sara and me swooping and swooning to Beiderbecke’s arrangement of “Tain’t So, Honey, Tain’t So” sung by Bing Crosby, then Sara and me backing up Rose, then the three of us behind Isabel, then finally Ken joining the women to Crosby’s “Because My Baby Don’t Mean Maybe Now.” I began to sense that the dark subtext behind the movement would never come through in the sprightly dancing, and I wrote in a narrator to account for the reservoir of emotion that prompted “The Bix Pieces”.

I hated to tap dance when I was a kid.

Says she, and I proceeded to do just that.

But this dance is about remembering. My tap dancing lessons, my baton twirling lessons, my acrobatics, the hula-hula. My father.

As the Adagio from the third quartet of Haydn’s Opus 76 begins, she explains that much of the dancing was made to this adagio, because I did not want to be too literal in following the Bix music. You can begin to see as Ken dances in the vernacular and Rose in ballet style:

Chassee is really a slap ball change: Exactly and not all the same.

All things are related, and as the Haydn winds down, she observes that its theme was a folk melody existing long before Haydn. There is continuity and development in all things:

For while my father died this spring, my son was born.

And then comes Part Three, a very short revision of the dancing in “Because My Baby Don’t Mean Maybe Now,” this time reset to the John Coltrane “Abide with Me”.

I am grateful to Joe Giordano for the gift of Twyla Tharp’s biography.

Bix, Rogue, or Hero?

In the book “Rogues and Heroes from Iowa’s Amazing Past” (Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, 1972), the author, George Mills, provides brief biographies of important or notorious people born in Iowa. The book consists of 18 chapters, each chapter dedicated to one town. Chapter 18 focuses on Davenport. One of the entries in the chapter is, as expected, Colonel Davenport. Another entry is entitled “If that Boy Had Lived…“The boy is Bix and there is a short account of his life illustrated with Bix’s famous picture from 1921. The title of the entry is taken from Louis Armstrong’s quotation, “If that boy had lived, he’d be the greatest“.

Iowans To Be Proud Of

In the book “Iowa Pride” (Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, 1996), the author, Duane A. Schmidt, celebrates the accomplishments of famous Iowans. The book is divided into three parts:

- Iowans Who Made It Here,

- Iowans Who Made It Elsewhere

- Iowa Firsts.

We find, in the second group, an entry entitled “Bix Beiderbecke (1903-1931), Renowned Cornet Jazz Stylist“. The two-page biography is preceded and followed by quotes from Louis Armstrong. “All I’ve ever called the dear boy was Bix… just that name alone will make one stand up.” “And when he played-why, the ears did the same thing.” The author provides a short phrase summarizing the achievement for each famous Iowan. In the case of Bix, this reads “Created a unique cornet jazz style“.

There are many other famous Iowans included in the book. I only cite a few, in subjects that are of special interest to me. John Vincent Atanasoff (“invented the digital computer“); Walter A. Sheaffer (“invented the first practical self-filling fountain pen“); Frank H. Spedding (“co-invented the production process for pure uranium“); James Van Allen (“discovered earth-encircling radiation belt“); Lee Deforest (“father of the wireless, commercial radio, and talking pictures“); Glenn Miller (“invented the big band sound“); John Wayne (“Academy Award-winning actor“).

Bix in “The Palimpsest”

“The Palimpsest” was a publication of the Division of the State Historical Society of the Iowa State Historical Department. The magazine was published from 1921 to 1995 under the Palimpsest name, but was changed to “Iowa Heritage Illustrated” in 1995. The July/August 1978 (Volume 54, Number 4) issue has a 12-page article entitled “In a Mist: The Story of Bix Beiderbecke” by Darold J. Brown. The article is a brief biographical account and contains several well-known photographs.

The content page of the magazine explains the meaning of the Palimpsest.

In early times a palimpsest was a parchment or other material which one or more writings had been erased to give room for later records. The history of Iowa may be likened to a palimpsest whcih holds the record of sucessive generations.

Bix and The Down Beat Hall of Fame

In 1962, Bix was elected by the readers into the Down Beat Hall of Fame. A list of all the awardees, beginning in 1952 with Louis Armstrong, is available. An article about Bix as a Jazz Hall of Fame artist is available on the Down Beat Jazz Magazine website. Also available on the Down Beat website is an article by Gilbert Erskine from the August 1961 issue of the magazine. Erskine provides an interesting account of the activities of Bix and other members of the Jean Goldkette Orchestra at the Blue Lantern Inn at Hudson Lake in the summer of 1926.

Two Victor “Best Seller” Records

The August 1927 Victor Catalogue lists on p. 5 the Twenty “Best Sellers”. Record number 13 has “Hoosier Sweetheart” by Jean Goldkette and His Orchestra on one side and “What Does It Matter?” by The Victor Orchestra on the other. Record number 19, “I’m Looking Over A Four Leaf Clover by Jean Goldkette and His Orchestra on one side and Roger Wolfe Kahn’s “Yankee Rose” on the other. Two best sellers with Bix in them!

I am grateful to Rob Rothberg for making available to me a copy of the pertinent page of the Victor Catalogue.

The Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Festival on Public Television

Iowa Public Television videotaped all the LeClaire Park performances of the bands that played at the 25th Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Festival (1996). A two-hour video cassette with performances of several of the bands is available for sale from IPTV. In addition, several thirty-minute segments of performances by one single band have been shown in various public television stations around the country. I have been informed of such broadcasts in Minneapolis, MN (mid to late 1997) and in Providence, RI (mid 1998). IPTV presented each band with a videotape of all the sets they performed in LeClaire Park at the Festival.

A Photograph of Bix in the New York Times.

The Arts and Leisure section of the New York Times of January 3, 1999 (first Sunday Times for 1999) carries a story by Richard Sudhalter about black and white jazz. The story is illustrated with three photographs: one of Louis Armstrong with the caption:

Louis Armstrong was a progenitor of his music’s vocal tradition and a jazz artist who showed unhesitating respect for the best white musicians. One of Bix Beiderbecke (quite large, 7.5 x 8.5 in) with the caption: The cornetist Bix Beiderbecke: posterity has little recorded evidence of his prowess, but pioneer black jazzmen knew it well”; and one of Jack Teagarden with the caption: The trombonist Jack Teagarden: You an ofay, I’m a spade. Let’s blow! Armstrong allegedly said, with much affection.

The Lincoln C. Selleck “Bix Lives” Jazz Award

The purpose of the Award is to encourage students under the age of 21 to “explore early American jazz, particularly that of the legendary jazz cornetist Bix Beiderbecke, by awarding a $400 First Place Award and a $100 Second Place Award annually to young musicians who demonstrate talent in playing Bix’s music.” Lincoln C. Selleck was a jazz enthusiast, writer, and naturalist. He was one of the founders circa 1945 (together with Dick Hallock and Howard Linley) of the low-profile “W. O. B.” (Worshippers of Bix club). The distinguished panel of judges consists of Dick Hallock, jazz critic and author; James Lincoln Collier, jazz historian and author; Dave Robinson, traditional jazz educator and musician; and Jon Milan and Howard Linley, traditional jazz musicians. Applications for the current year’s award, to be presented in January of 2001, are invited from all young musicians up to age 21. Students of traditional jazz age 21 or under who play a traditional jazz instrument are invited to apply for the 2000 Lincoln C. Selleck “Bix Lives” Jazz Award.. There are no entry fees. For application details, please see http://hometown.aol.com/yogi108/music1/index.htm.

The deadline for receipt of completed applications is October 1, 2000; the award winners will be announced by December 31, 2000, and the award will be presented in late January 2001. Jazz Youth Group Leaders or Educators may request application kits for the award for distribution to their students. An audio cassette of selections of the music of Bix Beiderbecke, as well as lead sheets for a number of Bix’s tunes, is available to jazz educators or youth group leaders on receipt of a written request and $5 in stamps to help cover mailing and duplication costs.

Requests for the application materials should be addressed to Thomas Selleck, Lincoln C. Selleck “Bix Lives” Jazz Award, P.O. Box 541, Fairfield, IA 52556. Website: http://hometown.aol.com/yogi108/music1/index.htm Email: [email protected]. For more information, please call Thomas Selleck or Marilyn Ungaro at 515-472-6003.

1998 Award

The two award winners were announced on December 15, 1998. The first-place award was won by 17-year-old Russell Baker, a trumpet player and a physics freshman at Columbia University. The second-place award was won by another 17-year-old youngster, Joseph Howell of Porterville, California.

1999 Award

Three Californian Teens Win Prizes In Lincoln C. Selleck “Bix Lives” Jazz Award Competition. Gordon Au, a trumpet and cornet-playing sophomore at U.C. Berkeley, has taken top honors in the second annual Lincoln C. Selleck “Bix Lives” Jazz Award Competition. His brother Brandon, a 16-year-old trombone player from Carmichael, California, tied for second place with 13-year-old Jazz Pianist David Hull from Fresno, California. The annual competition encourages traditional jazz in young musicians and awards a $400 First Place Prize and a $100 Second Place Prize.

The award was established in memory of jazz enthusiast and writer Lincoln C. Selleck in order to perpetuate his passion for the classic jazz of the 1920s and ’30s.

First-Place Winner Gordon Au has been playing traditional jazz trumpet and cornet since age eight. He credits his early exposure to trad jazz to his uncle Howard Miyata, who currently plays trombone with the High Sierra Jazz

Band. A former leader and performer with the Sacramento Jazz Society’s official youth band, the New Traditionalist Jazz Band, Gordon has played at numerous jazz jubilees, and in May of this year, he will play at the Sacramento Jazz Jubilee as a featured ‘Jazz apprentice’ performing with a professional band.

Second Place Winner pianist David Hull, age fourteen, was guided into the world of jazz at a young age by his father Ed. David has appeared at many jazz festivals, including the Sacramento Jazz Jubilee, the Suncoast Jazz

Festival and the Gateway Jazz Festival. He currently plays with the trad jazz Hull’s Angels Band and attends the Bullard T.A.L.E.N.T. Middle School in Fresno, California.

Tied for Second Place, Brandon Au has played trombone with his brother Gordon in the New Traditionalists Jazz Band since 1993. His trad jazz training started at age 12 and under the tutelage of musicians such as Bill Allred, leader of his Classic Jazz Band, Brandon continues to polish his skills.

An Incident in Princeton

James Stewart and Jose Ferrer were undergraduate students at Princeton University during the late ‘twenties and early ‘thirties. They belonged to the Charter Club. In his book “James Stewart, A Biography”, Turner Publishing, Inc., Atlanta, Georgia, 1996, Donald Dewey relates a visit by Bix to the Club.

If the Charter Club did not have one defining characteristic, it helped for members to like music. When Stewart wasn’t entertaining with his accordion, he was swapping musical notes in the club’s quarters with Jose Ferrer, the future actor, then preoccupied with leading a dance band.He also had a hand in planning the club’s elaborate jazz weekends for which some of the biggest names in the business were hired. On May 2, 1931, for instance, Charter sponsored a weekend party bill that included Bix Beiderbecke, Bud Freeman, Jimmy Dorsey, and Charlie Teagarden.

The weekend gained a footnote in the Beiderbecke story when the trumpeter, already oiled by a flask from which he had been sipping all evening, wandered off to another house, where he sat down at a piano and began to play a series of original, mesmerizing compositions that were never written down, let alone recorded. Later that Sunday morning, he had to be pulled off the street for flashing his flask in front of scandalized Princetonians on their way to church. It was partly because of this incident that a campus periodical admonished Charter a few weeks later for its spending on the weekend parties.

Just when the time will come when the clugs realize that they do not have to vie with New York debutante parties in elaborateness and splendor, is problematic, but it is bound to come”, warned the Prince.

A Poem for Bix

Michael Longley is an Irish poet, born in 1939, who has written poems (such as Cease Fire and Peace) about the problems in Northern Ireland. In 1992, he received the prestigious Whitbread Poetry Prize for his work Gorse Fires. Michael Longley wrote the poem “To Bix Beiderbecke”, a short (ten-line) poem honoring Bix’s genius for composition and improvisation.

A Poem About Bix’s Piano Music

On Sunday, August 1, 1999, at the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Festival in Davenport, Iowa, David Jellema, Archivist at the Center for Popular Music, Middle Tennessee State University, cornet player, and member of the New Traditional Jazz Band, read a poem written by his father, the poet Rod Jellema. The poem has not been published yet. Through the courtesy of David and Rod, I am providing the complete text of the poem below.

BIX BEIDERBECKE COMPOSING

A SUITE FOR PIANO, 1930-1931

mist, candlelights, cloudy, flashes,dark

by Rod Jellema

Some aura, thin and far ago,

the flutter of lights that plays

off the side of the eye

and darts away just when a child

will quickly turn the head to catch it.

He feels for keys and the chords shiver

like that, a mist of light

that catches Eden’s first breath.

Maybe it startled the first time he saw

lights in the distance at night,

empty factories, houses lit low

and lonely down the river

from the docks of Davenport while boats

cried their horns all over black water.

Or was it candlelights one starless night,

nodding off one by one in the glass

of the dining room window, small tongues

of fire down a twisting road

that he looked for years later, outside,

taking Vera for a drive in his father’s

1920 Davis 8. The road never appeared.

Ivory keys in hollow rooms. If only

his fingers will see the sounds to take.

To him it’s a matter of spaces,

he dares to know the spaces in his head

but some days it’s cloudy. And anyway

he has to find with his fingers

those notes the spaces mean, touch them

as though they’ve never before existed.

Too late to learn Ravel’s way there

on paper. Twenty eight and dying of booze.

Through eight fogged years of bandstands

and jams, he caught his music in flashes,

blew instant recompositions of themes

that he bent through silver, mixing colors

quick, before the phrases could die

by hanging themselves in clouds of smoke

and ash over the seas of laughing faces

deaf and adrift on a thousand lost dance floors.

When even that holy agitation of the flashes

clouded in, he worked anyway to lengthen

their glints through a whole piano suite

of broken light, bad gin and the shakes

on any borrowed pianos he could find.

Shaded from morning stabs of light,

he got back to where he was going all along,

the dreaming mind, the diamond-making dark.

Copyright 1999 Rod Jellema. I am grateful to Rod and David Jellema for providing me with a copy of the poem and for their generosity in allowing me to include it here.

A Swedish Poem About Bix

Gunnar Harding (b. 1940), a well-known Swedish modernistic poet, has written a very nice poem (in Swedish) about Bix, called “Davenport Blues, BIX BEIDERBECKE (1903-1931)”. It was published in his book “Gasljus” (1983). Gunnar Harding is especially famous for his tours, where he has been reading his poetry accompanied by a jazz band.

Five Poems About Bix

Ben Mazer is a well-known poet, a former student of Seamus Heaney at Harvard University, widely published in American and British periodicals, and the author of one published collection of poems, White Cities (Ben Mazer, Frank Parker (Illustrator) / Paperback / Barbara Matteau Editions / February 1995). Mr. Mazer has written a sequence of five poems about Bix Beiderbecke, all of which have been published in well-known British and American literary periodicals. The pertinent references follow.

FIVE POEMS ABOUT BIX BEIDERBECKE

Mazer, Ben. “Bix Beiderbecke (1903-1931).” The Dark Horse (Scotland), No. 5,

Summer 1997; pp. 16-17.

Mazer, Ben. “Davenport.” Press (New York, NY), Issue 6, 1997; p. 43.

Mazer, Ben. “White Jazz.” Verse (Williamsburg, VA & Scotland), Volume 14,

Number 3, 1998; p. 2.

Mazer, Ben. “Bix in Amherst.” Verse (Williamsburg, VA & Scotland), Volume

14, Number 3, 1998; p. 3.

Mazer, Ben. “Royal Garden.” Stand (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), Volume 39,

Number 3, Summer 1998; p. 36.

Ben kindly gave me permission to reproduce here an excerpt from his poem “Bix Beiderbecke (1903-1931)”:

My Wolverines – we were the living proof

the idiom of jazz was universal.

I led the young men with my silver horn

improvising records; as archetypal as

the first ice skater on a frozen lake

I was Hans Brinker at the brink of jazz –

modern, yet somehow cold and dark as winter;

almost anonymously at life’s center.

I am grateful to Ben Mazer for the detailed bibliographic references about his poems.

Ode to Bix

This composition by Earl A. Rohlf is, as described in the sheet music published by Polecat Records, “A Collection of Piano Music written in the style of Bix Beiderbecke’s piano music.” Earl A. Rohlf was born in Davenport, Iowa in 1907. His older brother, Wayne, was one of Bix’s classmates and played trumpet. According to the liner for the sheet music, Earl was a talented pianist who “attended the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago. Later on he was a staff pianist, arranger, and composer for several radio and TV stations in Cleveland, and taught both piano and organ.” “Ode to Bix” was composed around 1974 and consists of four parts.

- Bix Bash

- Bix Lives

- Ode to Bix

- Rhapsody for Bix

The sheet music for Ode to Bix was published on December 9, 1995, by Polecat Records, 3730 Fairlawn Drive, Minnetonka, Minnesota 55345.

A Tribute to Bix in Ascona

The yearly Ascona New Orleans Jazz Festival will take place this year from June 25 to July 4, 1999. This is the 15th year that jazz musicians and fans from all over the world will converge in this exclusive resort town in Switzerland. There will be tributes to three giants of jazz, Bix Beiderbecke, Duke Ellington, and Jelly Roll Morton. The tribute to Bix will feature Lino Patruno and the Red Pellini Gang with a special appearance by the amazing Spiegle Willcox.

Bix’s First Recording and the Gennett Richmond Studio

Bix’s first recording was made on February 18, 1924, in the Richmond, Indiana, studio of Gennett Records, a subsidiary of the Starr Piano Company. The Wolverines recorded four sides – “Fidgety Feet”, “Lazy Daddy”, “Sensation Rag”, and “Jazz Me Blues”. The band made several takes of “Lazy Daddy” and “Sensation Rag”, but all were rejected. On the other hand, “Fidgety Feet” and “Jazz Me Blues” were pressed and released in May 1924 on the blue Gennett label. Although this date must be viewed as a “first” for Bix’s jazz legacy, by 1924 a series of legendary jazz figures and bands already had recorded for Gennett Records: the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band (with a young Louis Armstrong), Jelly Roll Morton, and Doc Cook and His Dreamland Orchestra (featuring Freddie Keppard and Jimmy Noone). A very interesting and comprehensive account of the history and activities of the Gennett Studios is given by Rick Kennedy in his book “Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy”. A briefer but quite useful account can be found on a website entitled “The Cradle of Recorded Jazz“.

A Fictional Story About the Last Days of Bix

Sheryl Smith has written a fictional short story about the last days of Bix’s life. The complete story -entitled “Bix: To What End?”- is available on the internet at http://www.testdesigns.com/bixstory.htm

Hoagy, Bix and Wolfgang Beethoven Bunkhaus.

The Mark Taper Forum Theater, located in the Los Angeles Music Center,opened in 1967. The productions staged in the Forum range from the classics to the avant-garde. In the 1980-81 season, the musical production “Hoagy, Bix and Wolfgang Beethoven Bunkhaus” was presented. The musical drama was written by Adrian Mitchell and was produced by Steve Robman. Richard M. Sudhalter was the musical director. The band he assembled for the show included Dave Frishberg, the author of “Dear Bix“.

The following is an almost verbatim transcription of an account kindly provided to me by Richard M. Sudhalter.

““Wolfgang Beethoven Bunkhaus” was the pseudonym under which the cellist, pianist and composition student William Ernest Moenkhaus wrote satires, nonsense plays, and neo-dadaist poetry for The Vagabond,Indiana University’s student literary magazine of the 1920s. Son of an IU professor, he did part of his education at a Gymnasium in Germany, transferring to Switzerland in autumn, 1914, after the Great War began. He was apparently exposed to the Dadaist movement then taking shape in Zurich – or at least its intellectual fallout – and brought its principles back with him when he returned to study music in Bloomington.

As can be read in Carmichael’s memoirs, Moenkhaus became intellectual mentor for a circle of students who hung out at the campus soda shopand luncheonette, the Book Nook. His rather fey manner, flair for mock-sententious aphorisms and aperÁus, and above all his obvious depthand brilliance, proved irresistible to the half-formed Carmichael. In an intriguing way he was the exact antithesis of Bix: “Monk” the creature of intellect, all left-brain domination, Bix was one of intuition. Moenkhaus learned music, understood theory (he notated several of Hoagy’s first pieces for him); Bix came to it almost entirely by instinct.

Together they formed a sort of yin and yang for Hoagy’s awakening consciousness. Hot music fascinated Monk (though his efforts to play it were ineffectual at best), especially its intuitive character. Bix, for his part, had a flair for the kind of imaginative reordering of the world of appearances, the fatalistic view of the universe, at the heart of Monk’s thinking.

The British poet and playwright Adrian Mitchell found this constellation fascinating. He linked Moenkhaus’s wit, moreover, to the surreal (and very British) humor of Edward Lear, the musical high-jinks of Gerard Hoffnung, and even (a bit of a reach, it always seemed to me) the zanier side of the Beatles. His idea in writing the Bunkhaus play was to use Moenkhaus’s work as a counterpoint to both the high seriousness of Bix music and Monk’s intellectual life, and the world of fancy that each, in its way, also embodied. Both, remember, were essentially dark spirits, haunted – even tormented – by heaven knew what inner forces. Behind the Book Nook carryings on, behind Dadaism itself, was a profound despair at the human condition. Bix, of course, was no intellectual; if he was aware of this kind of thing at all, it was something of an abstraction for him. But consider the emotional mix of his playing: sunlight breaks through its darkest moments: his basic optimism burned long after his aspirations faltered. But it is also no accident that in all Beiderbecke’s records there is not one moment of whoop-de-do fun, or unalloyed happiness. I think it well to pay heed here to Ralph Berton, when he talks about Bix’s shadowed obsession with music. I thought then, and still think, he was on to something.

The “drama with music” concept of Adrian’s play required jazz: not the denatured product used in Ain’t Misbehavin’, Jelly’s Last Jam, and other Broadway items, but real hot music. That meant a six-piece band onstage throughout most of the play, performing mostly Carmichael songs and a few jazz band numbers associated with Bix. Its first productionwas in a small pub theatre in London’s East End. The first U.S. production was at the Indiana Repertory Theatre – actually the remodelled Indiana Theatre, the very building in which Bix and Tram had joined Paul Whiteman in October 1927. I was arranger and musical director, but did not play in this production, which ran for some three weeks. All the bandsmen were Indianapolis musicians. A few of the actors – Jamey Sheridan, Armin Shimerman – turn up now and then on TV.

The Taper production in Los Angeles came some months later. The stage band was myself on cornet, Dave Frishberg singing and playing piano, Bob Reitmeier on clarinet and alto, Howard Alden (age 22) on banjo and guitar, Putter Smith (younger brother of Carson Smith) on bass, and Dick Berk on drums. The cast included the singer-cabaret artist Amanda McBroom. Mark Robman worked out an interesting idea for staging the musical sequences: every time the Bix character, played by Harry Groener, had to play some cornet, he would stand, horn at mouth, in the spotlight, facing the audience; I would stand, in darkness, back-to-back with him, but costumed identically. Then we would simply revolve, as if on a pedestal, bringing me into the spotlight and him into shadow. I’d play the solo – I remember doing “Singin’ the Blues” and “I’m Comin’ Virginia,” among others – then we’d revolve back, and I’d melt into the darkness off stage while Groener carried on with his lines.

The musical side of the show got mostly rave reviews, but Mitchell’s play took a critical pasting. Unfairly, I thought: he’d tried, very imaginatively, to bring off a difficult concept, blending the Weltschmerz of the Bunkhaus humor (even casting some of the episodes as puppet-show plays within the play) with the Beiderbecke tragedy, all against the Carmichael coming-of-age motif. There were things that didn’t work, sure – but I thought then, and still do, that it was a very ambitious undertaking and deserved better treatment than it got.“

Next, it is interesting to point out the connection betwen this show and the CD Dick Sudhalter and His Friends “With Pleasure”. According to Leonard Feather who wrote the liners for the original album included in the CD: “Before the show closed, it became apparent to Sudhalter that the combo he had assembled was too good not to be preserved. With the exception of Dan Barrett and Daryl Sherman, all the participants here were his colleagues in the show. Instead of confining himself to Carmichael songs for this album, he dipped into the vast reserve of early jazz/pop standards stored in his capacious memory. Several of the selections are clearly a nod to Bix Beiderbecke.” Thus, we can hear interesting renditions of “From Monday On“, “Blue River“, “Waiting at the End of the Road“, and “I’ll Be A Friend “With Pleasure“”.

Finally, it is noteworthy, that almost twenty years after his involvement with the show centered around Hoagy, Dick Sudhalter is currently writing a biography of Hoagy’s. I quote form Hoagy’s web site: “Trumpeter-historian Richard M. Sudhalter has signed with Oxford University Press to write a full-length biography, Star Dust: The Life and Music of Hoagy Carmichael, to be published in late 1999. Mr. Sudhalter’s research will draw on interviews, archival material, recorded music, and the composer’s own personal papers. The book will also include more than three dozen photographs, and careful analysis of Hoagy Carmichael’s music and methods.” The publication of the book is part of the centennial celebrationof Hoagy Carmichael’s birth. As another part of the celebration, Dick Sudhalter with singer Barbara Lea and an all-star band of European Jazz musicians will present, in late 1999, a new show, “Along the Stardust Road”, in Hamburg, Berlin and other major cities in Germany, Austria, and the Benelux countries.

I acknowledge with gratitude Richard M. Sudhalter’s contribution. Without his help, this section could not have been included here.

Enrico Borsetti kindly sent me scans of the program for the English production of the play. They follow here.

The Hoagy and Bix Company.

This item is taken from Hoagy’s centennial celebration web site.

“Columbia Artists Management Inc., Concert Productions, and The Hoagy & Bix Company will present a big band centennial celebration tour featuring the music of Hoagy Carmichael. This tour will play in at least 45 cities in the United States and will begin in Los Angeles in January 2000.”

The Original Bixography.

In the early 1940’s, the Canadian Bixophile Edward Moogk organized “The Bix Beiderbecke Club”. The Club was “Dedicated to the Memory and Works of Bix Beiderbecke”. Wayne Rohlf, who had attended high school at the same time as Bix, was the first Honorary President. The membership was small (22 members in February 1943). One of the members at that time was Joe Giordano, Bixophile extraordinaire, collector, and writer.

The club published a monthly newsletter entitled “BIXOGRAPHY”! The name had been coined 56 years before I launched the “Bixography” web site! I hope this is not viewed as plagiarism or copyright infrigement. I plead innocent! It is only this week (May 19, 2000) that I learned of the existence of the”Original Bixography” through the courtesy of Joe Giordano who sent me copies of two issues of the newsletter.

The newsletter consisted of original contributions and reprints of articles published in magazines. As an example, the contents of the February 1943 issue was: Club News and Members; A List of Available Bix Records; High School Days with Bix, by Wayne H. Rohlf; Bix Stories, by Eddie Condon and Frank Norris; Beiderbecke Discography, by George Hoefer, Jr.

I am grateful to Joe Giordano for sending me copies of the “Bixography”.

Bix Beiderbecke Legacy Stage Show.

The New Wolverine Orchestra will present the second edition of their Bix Beiderbecke Legacy stage show on 28th July, 1999 in Sydney’s “Independent Theatre”. The title for this year’s edition is “The Story of Bix“. This will be a 3-hour theatrical presentation tracing Bix’s life and recording history, with stage lighting, costume changes, etc. The show is narrated by one of Sydney’s top stage/radio/TV/film actors, John Derham, following a script prepared for him by the show’s promoter, John Buchanan. While the orchestra plays, a giant projection screen behind the band shows “blow-ups” of photographs of Bix.

The tunes, ranging from Bix’s first to his last recording, are representative of all the facets of his career: piano solos; Wolverines; Rhythm Jugglers; Goldkette; Trumbauer; Tram, Bix and Lang; Bix & His Gang; Whiteman; The Hotsy Totsy Gang; Hoagy’s Orchestra; and Bix’s own orchestra.

Addendum, August 7, 1999. Trevor Rippingale writes: “The Story of Bix” was a sell-out : 350 people and bookings had to be turned away in the last few days. Audience response was absolutely overwhelming: a very emotional reaction to the music, the narration and the giant photos of Bix and the boys behind the band as we played. It really inspired us to play better than we’d hoped…and not without a tear of two among the band. The dedication to Phil [Evans, ed.] (whom we’d all met) both in the programme and from the stage heightened this emotion for us. Our cornetist Geoff Power won ovations for his note-for-note Bix solos playing his 1920s Conn Victor American long cornet, as Bix so often used. Being quite young and with his hair parted in the middle, he also looked uncannily like Bix. One of the best received numbers of the whole night was the trio piece, “Wringin’ an’ Twistin’ ” which I did on C melody sax playing Tram’s solo, with Robert Smith’s note for note piano solo (as played by Bix originally), and drums accompaniment (our guitarist unfortunately opted out) plus the 2 bar cornet break at the end. The narrator drew attention to my 1925 Conn C melody sax, which I also played in “I’ll be a Friend With Pleasure”, “Singin’ The Blues” and “The Japanese Sandman”: all Tram solos. The audience responded magnificently, as they also did for the 1924 Conn bass sax which I brought out for “At The Jazz Band Ball”, “Changes”, “Since My Best Gal Turned Me Down” and “Riverboat Shuffle”. Its good to get recognition for these lovely old rare instruments. Our pianist, Robert Smith, deserves great praise for his faithful ten-finger re-creations of Bix’s piano solos : “In A Mist”, “Flashes”, “In The Dark” plus “Big Boy” and “Wringin’ an’ Twistin’ “.The above account is an almost verbatim transcription of an e-mail (7/8/99) from Trevor Rippingale. I am grateful to Trevor for providing the information.

A German Radio Play About Bix

Ror Wolf: Leben und Tod des Kornettisten Bix Beiderbecke aus Nord-Amerika.

(Schöffling & Co., Frankfurt/Main 2000, 285 pp., ISBN 3-89561-317-7).

This book contains radio plays from 1969 to 1997 by the German author Ror Wolf (b. 1932). One of the plays (pp. 155-203) bears the same title as the book. The Bix radio play was written in 1985/86 and first broadcast on February 12, 1987. Here we meet people like Tram, Hoagy, Mezz Mezzrow, Jimmy Mc Partland, Pee Wee Russell, Paul Whiteman – and of course Bix himself – telling the story of Bix Beiderbecke. This is a very nice radio play, in great part because the author is familiar with the literature about Bix, and consequently there is little if any fiction in it. As a matter of fact, parts of what the characters say are recognizable as quotes from books.

A CD is included in the book – unfortunately it does not contain the play about Bix. The play is available on a separate CD from another publisher: Leben und Tod des Kornettisten Bix Beiderbecke aus Nord-Amerika (Der Audio Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-89813-108-4).

In 1988, Ror Wolf was awarded the prize “Hörspielpreis der Kriegsblinden” for this radio play.

The above account is an almost verbatim transcription of an e-mail (9/2/01) from Anders Gustafsson. I am grateful to Anders for providing the information.

The First Discography of Bix’s Recordings.

The first issue of the French magazine “Jazz Hot” was published in March 1935. Starting in p. 17, Charles Delaunay provides a brief biographical account about Bix Beiderbecke. Two versions of the article are included in the magazine, back to back, one in French, the other the English translation. Although there are a number of errors of detail, by and large this is a remarkable account considering the time when the article was written (three and half years after Bix’s death), and the fact that M. Delaunay did all his research for the article while living in France. Some of the errors are fascinating in the sense that they reveal that the information was available but somehow got garbled in the process of crossing the Atlantic Ocean. For example, the engagement of the Wolverine Orchestra in New York is given as taking place at the “Arcadia” rather than the “Cinderella”. This shows that Delaunay had some information about the connection between Bix and the Arcadia Ballroom, but had the wrong city and the wrong year. Another interesting error relates to the composition and activities of the Wolverines. According to the article, the Wolverines were formed in 1922, included Benny Goodman and played on a riverboat that traveled between Grand Rapids and Chicago. This information is incorrect, but it is understandable how the errors came about. Indeed, Bix played with Goodman aboard the steamer “Michigan City” but the route was Chicago to Michigan City, the year was 1923 and the band was that of Bill Grimm. But the general circumstances are not totally wrong. It is also fascinating to see how some minute details are described correctly. An interesting example pertains to the question of the drummers in the Wolverine Orchestra. Here is the pertinent quote: “During the winter, the orchestra took a second drummer: Vic Berton who soon found an engagement for the orchestra in Chicago, but as nobody wanted to be separated from Vic Moore, the orchestra then included two drummers.” The Wolverine Orchestra never had an engagement in Chicago, but the account of the orchestra members not wanting to let Moore go is accurate. The discography entitled “Discographie de Bix et Trumbauer” includes the recordings of Bix with the Rhythm Jugglers, with the Gang and with His Orchestra and the recordings of the Frankie Trumbauer orchestra. The listings for the Jugglers (includes the statement that Howie Quicksell did not play because he was too drunk!) and for the Orchestra (including the speculation that perhaps Bix plays the piano solo in “I Don’t Mind Walkin’ in the Rain”) are complete. The listing for the Gang has all the recordings except “Margie”. The listing for Trumbauer’s orchestra contains not only the recordings with Bix but several recordings where Bix is not present and Andy Secrest plays the cornet.

All in all, considering the limitations of the time and place, Charles Delaunay has written a good brief biography and an excellent discography of Bix and Tram.

I am grateful to Jean Pierre Lion for his generosity in providing me with a copy of Delaunay’s article.

Playing Jazz in an Authentic 1920’s (Bixian) Style.

There are several contemporary bands that play what has become known as Dixieland jazz. They make appearances in their home towns and/or in jazz festivals, and seem to be fairly successful with their audiences. In my opinion, many of these bands play music which is as far removed from 1920’s traditional jazz as cool jazz or other abominations. I am very demanding when it comes to reproducing the jazz or dance band sound of the 1920’s. In this section, I will cite (in no particular order) some of the bands that, in my opinion, recreate faithfully the style of 1920’s jazz, in particular those that, in one form or another, pay homage to Bix and/or maintain his musical tradition. I do not pretend to provide an exhaustive list of all traditional jazz bands that play to my liking. I only offer a few representative examples. My apologies to the many excellent bands that I do not mention here.

The New Wolverine Jazz Orchestra.This is a group of Aussies from Sidney who are dedicated to “celebrate[ing] the music of Bix Beiderbecke

and the musicians and bands with whom he played.” “Enthusiasm for Bix and the music of the “Jazz Age” is the catalyst which unites and leads us to spend many hours listening to original recordings, selecting those that appeal, then transcribing and scaling them down into arrangements which maximize the sound of our small group, yet still preserve the spirit and feel of the era.” (This quote is taken from their home page). The band has made appearances at the 22nd, 25th, and 27th Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Festival. They will be coming to the festival again in 2000. The group has made six recordings some of which are available (see their home page and Trevor Rippingale’s personal page) by getting in touch with Trevor Rippingale, the “coordinator, not the leader” of this nice group. Jazzology has released their fifth CD, Roll On Mississippi, Roll On.

Beginning on March 10, 1999 the New Wolverine Orchestra did a “Bix Birthday Mini-tour” of Queensland, playing Jazz Clubs at Noosa Heads, Brisbane City and Surfers’ Paradise. A few years ago, they had celebrated Bix’s Birthday with a couple of concerts for the Sydney Jazz Club. Presently (April 1999), they are planning on celebrating Bix’s birthday every year.

The New Wolverine Orchestra’s latest CD, Volume 7: “Sydney to Chicago” is now (October 1999) available. According to the liners “We dedicate the first ten tracks to our “Patron Saint”, Bix Beiderbecke. Then follow ten tracks associated with other “greats” including Artie Shaw, Benny Goodman, Red Nichols, Pee Wee Russell, Bunny Berigan, Adrian Rollini, Bob and Bing Crosby,, and Australia’s own Frank Johnson and his fabulous Dixielanders. Perhaps the centrepiece of this CD is Geoff Power, our lead cornet since January 1998.” My personal favorites in this CD are Davenport Blues, Tia Juana, and Ida, Sweet as Apple Cider. In particular, the rendition of Davenport Blues is first-class. I find that many versions of this great tune fail to grasp the”spirit” of Davenport Blues; the New Wolverine Orchestra’s version captures Bix’s conception very accurately.

Vince Giordano. Vince is a musician to my taste. He is a real

traditionalist. He collected, from the time he was a teenager until the 1990’s over 30,000 arrangements played by the dance and jazz bands of the 1920’s and early 1930’s. As a band leader, he insists on all musicians playing note by note, including solos, the original arrangements he uses. Vince Giordano’s Nighthawks have recreated in person and in recordings the great music from the California Ramblers, the Jean Goldkette Orchestra, McKinney’s Cotton Pickers, Red Nichols, and other giants from the 1920’s. Vince plays most bass instruments -bass saxophone, tuba, string bass. He collaborated with Bill Challis (yes, the great arranger for the Jean Goldkette and the Paul Whiteman orchestras) in “The Goldkette Project” (see the page on recordings). He was one of the musicians in the soundtrack of the film “Bix: An Interpretation of a Legend“. Chip Deffaa has a good account of Vince’s activities (up to 1984) in the book “Traditionalists and Revivalists in Jazz”, The Scarecrow Press and the Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers, Metuchen, N. J. 1993. As a matter of fact, the dust cover of the book is a photograph of Vince Giordano playing the bass saxophone. Currently, Vince brings his unique skills as jazz musician and collector extraordinaire of stock and special arrangements to his position as an archivist for BMG Entertainment. Although this is a full time occupation, Vince finds enough time to play every Monday and Thursday nights at the Cajun Restaurant, 8th Avenue and 16th Street in New York City. He also does gigs with various groups who play in the traditional mode. Thus, he appeared with Ralph Norton and his Varsity Ramblers at the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Festivals of 1997 and 1998. Vince’s full Nighthawks band appeared in March 2001 at the the Tribute to Bix in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

Addendum, 12/21/02. The August 12, 2001 edition of the New York Times includes an article by David Wondrich entitled “Jazz Is Young Again Under the Nighthawks’ Wings.” here is the complete text of the article. “When Vince Giordano’s Nighthawks are playing, it’s easy to

lose track of time: not just minutes, or hours,

but whole decades. For most people who listened to jazz during its first

golden age, roughly 1924 to 1934, it meant a dozen-odd white guys in

waiter suits, reading music off stands while the patrons ate, drank and

danced.

Cajun, the slightly down-at-the-heels Creole restaurant in the Chelsea

section of Manhattan, where Mr. Giordano’s band (essentially white guys in

tuxes) holds forth two nights a week, sells its liquor legally and has no dance

floor, but it’s otherwise exceedingly easy to mislay 70 years there —

especially when the Nighthawks, all 11 of them, rip through an old

barn-burner like the Casa Loma Orchestra’s “Casa Loma Stomp” from

1930, or ease into the Jean Goldkette Orchestra’s lovely 1927 arrangement

of “Clementine From New Orleans.” In their hands, jazz is young again, full

of ginger and pep and still possessed of a certain innocence. It’s difficult not

to agree with the film critic Leonard Maltin, a fan, when he says: “Their music

makes me feel good. It lifts my spirits.”

By rights Mr. Giordano, 49, should be a star. Not because very few people

play the bass as well as he does (or the tuba, or the bass saxophone; he

plays seven instruments that he’ll admit to). Not because after 30- odd years

onstage he knows as much about leading a jazz band as any man alive.

Not even because he can keep a topnotch band together, no easy task in the

best of circumstances and an almost heroic one when you factor in the

Nighthawks’ low pay and other commitments — these are professional

musicians who are very much in demand (and then there’s Mr. Giordano’s

day job, as an archivist at BMG Records, and the other bands he plays in).

Nor is it because he has many prominent fans, although on any given night at

Cajun you might see Mr. Maltin or the cartoonist R. Crumb or the director

Mel Brooks or any one of the number of jazz writers, filmmakers, actors,

radio personalities and other time-travelers who make up much of the

Nighthawks’ regular clientele.

Mr. Giordano should be a star because he is a star. He has the charm,

confidence and bearing of a star, a star’s sense of mission and purpose. He

even looks like a star, at least by the standards of, say, 1931.

But it’s not 1931, and, in the modern world of jazz, Mr. Giordano has two

strikes against him. First off, the Nighthawks are a revival band. According

to jazz orthodoxy, the revival band stands somewhere in between the circus

band and the society orchestra: a novelty outfit made up of amateurs,

has-beens and never-wases, good only for amusing tourists and titillating

retirees with a whiff of their long-past youth. For some reason, it’s

acceptable to live within the musical territory carved out by Thelonious

Monk and Miles Davis and John Coltrane a generation or two ago, but not

that of the generations before them.

Yet a repertory band can still thrive, if not always with the critics. Wynton

Marsalis has led the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, unabashedly modeled on

Duke Ellington’s great band of the 1940’s, to such heights of acclaim that

Jazz at Lincoln Center, its parent organization, is building it a

100,000-square-foot, $115-million concert hall, which is scheduled to open

in 2003.

This success has had a certain trickle-down effect, as Mr. Giordano readily

acknowledges: “Wynton has made my life much easier.” When he assembled

the current “herd,” as he calls it, of Nighthawks, at the end of 1998, he hadn’t

had a band together in four years.

But Mr. Marsalis’s idea of a repertory band and Mr. Giordano’s are two

different animals, and that’s not just because the center of the Lincoln Center

band’s sound is in the late 1930’s, a decade later than that of the

Nighthawks. For one thing, the Lincoln Center players enjoy a generous

latitude in bringing modern techniques and ideas into the old music, ensuring

a good deal more solo pyrotechnics than you would have heard in the

music’s day. The Nighthawks do not. “I prefer sticking closer to the score,”

Mr. Giordano said. In fact, when the director Terry Zwigoff needed

somebody to create precise renditions of a few classic jazz 78’s for the

soundtrack of his new film, “Ghost World,” he turned to Mr. Giordano.

To be a Nighthawk isn’t easy. As Dan Levinson, the band’s principal clarinet

soloist, pointed out: “It’s very hard to play that music accurately and to

disregard all of the changes in music that have taken place since it was

originally performed. You really have to forget about swing and be-bop and

all the subsequent permutations of post-1934 jazz.”

In fact, many of the arrangements the Nighthawks play are straight

transcriptions from the original records, solos and all. Others, however, are

not — and it’s a mark of the band’s command of the idiom that you find it

hard to tell which solos are old and which are new. “I have no doubt this

would have been one of the best bands in the 20’s,” said Sherwin Dunner,

the producer of Yazoo Records’ well-received “Jazz the World Forgot”

series.

Yet paradoxically, given the Nighthawks’ concern for authenticity, their music

is in practice entirely free from the eat-your-vegetables quality that

sometimes colors the Lincoln Center band’s efforts. Partly this is because

you can experience it sitting at a table with a drink in your hand (if you can

get a reservation, that is; space at the Cajun is limited, and they fill it).

Mostly, however, it has to do with the Nighthawks’ repertory.

When the Lincoln Center band chooses an old piece to revive, you can be

sure it will be a classic: this season the group will be playing music of Duke

Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, Woody Herman, and John Coltrane, among

others. Pretty safe ground. The Nighthawks are up to something different.

Mr. Giordano is a dedicated, even obsessive, collector of old music. The

basement of his house in Brooklyn is packed with more than 30,000 fully

indexed band arrangements. As a result, his band book runs to four fat

volumes, more than a thousand items, with plenty of surprises.

The jazz establishment would have no problem with many of these items. The

Nighthawks play plenty of Ellington, Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong and

so forth. But then there’s the other stuff. Take “The Moon and You,” their

theme song, a bright, catchy fox trot composed by Leroy Shield for the 1931

Laurel and Hardy short “One Good Turn.” It’s precisely the kind of

confection that jazz critics consider lightweight — “dance music,” not jazz.

Yet in the Nighthawks’ rendition, there’s a surprising amount of power under

the music’s sunny exterior; it’s as if you opened the hood of one of those cute

new Volkswagens and found a V-8 engine. “I like to mix it up — I don’t like

to be a jazz elitist,” Mr. Giordano said. “Everybody had their degree of

jazzness.” Listening to 1920’s pop records, that jazzness is often not

immediately apparent. Live, the Nighthawks bring it out. (You’ll never hear

Rudy Vallee the same way again.) The Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra

confirms, often gloriously, what we know about jazz’s history; the

Nighthawks challenge it.

Jazz tradition dictates that there is only one way to settle such philosophical

differences: a battle of the bands. I’ve long nurtured a fantasy of Vince

Giordano and his crew and Wynton Marsalis and his going toe-to-toe

onstage. Whether this (admittedly improbable) contest were to be held at

Lincoln Center or, better yet, at Cajun, it could run all night as far as I’m

concerned.

David Wondrich is the author of “Torrid Rhythm: the First Century of

Rock and Roll, 1843-1950,” to be published next year by A Cappella

Press.

On August 13, 2001 I sent in the following letter to the editor of the New York Times. The letter was not published.

“Dear Editor:

I was very pleased to read the laudatory comments of Mr. David Wondrich about Vince

Giordano’s Nighthawks. The praise is highly deserved. For the last thirty years, Vince, a

talented musician/collector/historian, has labored mightily for the preservation and

dissemination of the jazz legacy of the 1920s. I am also glad to see that Mr. Wondrich

refers to “Jazz” in the title of the article.

In the 1920s there was a continuum of styles going from hot jazz to bland dance band

music. Hot dance bands were somewhere in between. But, jazz was a strong component of

almost all styles of popular music. Both black and white musicians played hot jazz and

dance music. Examples of hot jazz bands are Louis Armstrong’s Hot Fives (black) and the

Original Memphis Five (white). Examples of dance bands are the Fletcher Henderson (black) and Jean Goldkette (white) orchestras. As a matter of fact, these two orchestras played in a”Battle of the Bands” in the Roseland Ballroom in New York in October 1926. Jean Goldkette, by all accounts, was the decisive winner, in great part because of the “hot”

musicians in the orchestra. The four bands had very different styles, but they all played

jazz.

Some critics and historians take the position that only black musicians played “real” jazz in

the 1920s, whereas white musicians, with the possible exception of a small portion of the

output of the legendary cornetist Bix Beiderbecke, played a pale imitation of jazz, or mostly

pop music. Ken Burns’ recent PBS program about jazz has, unfortunately, reinforced the

myth that jazz is an art form cultivated almost exclusively by black musicians.

I strongly disagree with this widely accepted notion. Bands of white musicians such as Red

Nichols and His Five Pennies, the Coon-Sanders Original Nighthawk Orchestra, the California Ramblers and the smaller groups derived from it, and last, but not least, the Jean Goldkette Orchestra, played a style of hot music which contained most of the elements of jazz, but derived more from the European musical tradition, and less from the blues. For various reasons, many jazz historians and scholars are reluctant to admit that a great portion of the music played by many white musicians in the 1920s was indeed a form of jazz.

The repertoire of the Nighthawks includes many tunes played by white dance bands from

the 1920s. I view the Vince Giordano Nighthawks as the 21st century equivalent of the

1920s Jean Goldkette Orchestra. Make no mistake: as beautifully articulated by Mr.

Wondrich, what the Nighthawks play at the Cajun on Mondays and Thursdays is most

certainly jazz.

Albert Haim

Addendum, December 21, 2002.

The “Goings On” section of the December 23 & 30, 2002 edition of the New Yorker includes

the following item.

****************************************

CAJUN

129 Eighth Ave., at 16th St. (691-6174)

It’s not as if Vince Giordano and the Nighthawks are obsessed with the music of the

twenties and thirties—they’ve even been known to slip in a number or two from the forties

as well. Manning the most unwieldy of instruments (bass, tuba, bass saxophone) as well as

a bulbous vintage Kellogg microphone, Giordano leads a tuxedo-clad twelve-piece band

whose ease with early jazz and swing breathes life into an overlookedera. Authenticity and

affection, rather than nostalgia and affectation, are what power this valuable and enjoyable

ensemble. They’re here on Mondays and Thursdays. The rest of the week features combos

fluent in Dixieland jazz and other improvisational sounds of New Orleans.

*********************************

A cartoon depiction of Vince Giordano with his instruments illustrates the column.

I think that the reporter hit the nail right on the head when he/she wrote,

Authenticity and affection, rather than nostalgia and affectation

Indeed, it is abundantly clear to anyone who goes to the Cajun any Monday or Thursday

evening -and you should when you are in town or nearby -that Vince and his fellow

musicians are driven by their love for the jazz and the hot dance music of the 1920s and

1930s and that they bring back the sound of “that overlooked era” in the most authentic

manner. The performance by the band is not an excuse for a “back to the past” sentimental

journey, but a living, dynamic demonstration that this music can be current and timely in

the 21st century. Vince and his fellow musicians understand the spirit and the historical

context of the music from the 1920s and 1930s and, thus, render it as a breathing,

flourishing presence for today’s audiences.

Links of interest about Vince Giordano are the following.

http://home.att.net/~vgiordano/

http://www.weglarz.com/dev/vince/

San Francisco Starlight Orchestra.This California based orchestra, founded by John Howard, consists of sixteen musicians who play original arrangements from “jazz age” orchestras such as Paul

Whiteman, Bennie Moten, Ben Pollack, Ben Selvin, and George Olsen. Since 1989, the orchestra performs the first Saturday of every month at the Recreation Center in Mill Valley, California. At the 1993 Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Festival, John was a guest conductor for an all-star 1920s’style orchestra assembled especially to play for the opening in Davenport of Avati’s film “Bix: An Interpretation of a Legend“. The San Francisco Starlight Orchestra has recorded four CD’s. They are available from Stomp Off Records or directly (check their home page) from Jim Brennan, the manager and tuba player for the orchestra. I have their delightful CD “Cheerful Little Earful” which contains several tunes associated with Bix, such as Clementine, Baltimore, and Bessie Couldn’t Help It.

Ralph Norton and His Varsity Ramblers.Thisband, from East Peoria, Illinois, has a good sounding name that reminds us of the California Ramblers and the smaller group, the Little Ramblers. Ralph, on the cornet, produces an excellent recreation of the special Bix sound, and, with such great musicians as Vince Giordano, who places a great value in the authentic 1920’s style, the band brings us back to the

Goldkette years. The Varsity Ramblers have made several appearances at the annual Tribute to Bix in Libertyville, Illinois and at the annual Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Festival in Davenport, Iowa. Ralph’s CD, The Moon and You, can be obtained by writing to Ralph C. Norton, 1204 Oakwood Road, East Peoria, Illinois 61611. One of the highlights of the 1997 Festival was the return of Bix’s cornet to Davenport to be housed permanently in the Putnam Museum. On the Saturday morning of the Festival, Ralph and his Varsity Ramblers, augmented by Spiegle Wilcox, played at Bix’s grave-site. Bix’s cornet was brought in and Ralph had the honor and privilege of playing it. It was a highly emotional experience for the band, the audience, and, in particular, for Ralph. For this solemn occasion, Ralph raised his playing to the highest level and treated the audience to a highly charged and moving performance.

The Charleston Chasers. This group of British musicians takes its name from the great American jazz band from the 1920’s (Red

Nichols, Miff Mole, Phil Napoleon, Benny Goodman, etc.) According to Brian Rust’s liners for the delightful CD “Pleasure Mad“, the new Charleston Chasers “are young musicians -three of them are women- who love the old style and have set out to give it a new lease on life.” The sound is very much the sound of the white hot dance bands of the 20’s and there is an underlying Bixian quality to several of the songs. There are two Goldkette sides – Proud of a Baby Like You and Clementine. Sean Bolan, the leader of the band and cornet player, does an excellent job in emulating Bix’s sound.

The Blackbird Society Orchestra. This is a group of eight to eleven musicians led by guitar and banjo player Richard Barnes from Aston, Pa. Richard Barnes tells me (e-mail of 3/28/99) that the inspiration for his orchestra comes from Vince Giordano’s Nighthawks. According the Working Bands Web Site “this great band authentically recreates the music of the Jazz Age. To assure authenticity in the performance of the music, The Blackbird Society Orchestra uses the original charts of such great bands as the Coon-Sander’s Nighthawks, California Ramblers, Paul Whiteman (with a young Bing Crosby and the Rhythm Boys), McKinneys Cotton Pickers, Jelly Roll Morton, New Orleans Rhythm Kings, Emmitt Miller, Benny Goodman, The Dorsey Brothers, Frankie Trumbauer, Bix Beiderbecke, The Wolverines, Louis Armstrong, Red Nichols and many more!” When interviewed by Floyd Murray of the Delaware County Daily Times (April 3, 1998), Richard Barnes stated: “We’re not a big band, or a Dixieland band…we perform the type of music that helped define the sound of jazz, and ushered in the first big bands of the thirties over ten years before the Big Band Era as we know it today would emerge.” Richard kindly made available to me a cassette of some of his studio as well as his live recordings. Among these I cite the Bix-related tunes “There Ain’t No Land Like Dixieland To Me“, “Happy Feet“, “Riverboat Shuffle” and “Singin’ the Blues“. The band has a nice sound quite reminiscent of the hot dance bands from the 1920’s.

Bix Played at Gertrude Seiffert Beiderbecke’s Wedding

Charles Beiderbecke, Bix’s grandfather, married Louise Piper in 1860. They had four surviving children: Carl Thomas, Ottilie, Bismark and Lutie. Carl Thomas Beiderbecke married Adele Seiffert in 1895. They had four daughters. One of them was Gertrude, born three weeks before Bix.

From February to June 1923, Bix lived with his parents in Davenport and worked at the East Davenport Fuel Company. Bix’s father was the manager of the company. It is during this period that Gertrude Beiderbecke, Bix’s cousin, married William D. Washburn. Bix played piano at the wedding which took place on May 3, 1923. The Davenport Democrat & Leader, a local newspaper, gave, in part, the following account of the wedding. “The ceremony was at 10:30 in the drawing room, the large south windows being used as a setting for the improvised altar, a profusion of spring flowers in peach and lavender hues giving the colorful touch to all the rooms in gracefully arranged bouquets in baskets and vases. Bix Beiderbecke, the cousin of the bride, was at the piano and played the wedding march as the bride entered on the arm of her father, Charles T. Beiderbecke, who gave her away.”I am grateful too Rich Johnson for a copy of the newspaper article.

Bix Beiderbecke Lithograph Print

“Rehearsing Davenport Blues” by Ben Denison (Denison Jazz Art) is a painting based on the recording session at the Gennett Studio’s in Richmond, Indiana 1925 when “Davenport Blues” was recorded. The musicians in the session were Bix Beiderbecke, Tommy Dorsey, Tommy Gargano, Paul Mertz, Don Murray, and Howdy Quicksell. Unfortunately for Howdy Quicksell, he arrived late and did not get to record Davenport Blues. Bix, Tommy Dorsey, Paul Mertz, Don Murray, and Howdie Quicksell are included in the painting. The back cover of “Bix: The Leon Bix Beiderbecke Story” by Philip R. and Linda K. Evans displays a photograph of the painting.

For an image of the painting go to

http://www.decadesign.com/scptest/0bixprintlg.jpg

A print (28″ x 49″) of this painting is available. $75.00 plus shipping ($10.00 – rolled in tube; $25.00 – flat in box). Contact: [email protected]

I am grateful to Daniel Kutsko for providing the information about the painting.

The Keeley Institute

Bix Beiderbecke broke down during the September 13, 1929 recording session of the Paul Whiteman Orchestra. Bix spent September 14 in his room at the 44th Street Hotel. Paul Whiteman went to see Bix and told him in no uncertain terms that he had to straighten out. The next day, Paul and Kurt Dieterle took Bix to Grand Central Station and put him on the train to Davenport. Once in Davenport, Bix spent several weeks at home trying to recuperate. He was weak and had pains in his legs. As Bix’s health was not returning, the family doctor advised that Bix hospitalized in a sanitarium. On October 14, 1929, Bix was taken to Dwight, Illinois for admission to the Keeley Institute, an alcohol recovery organization well-known throughout the midwest. Bix stayed in the Institute for four weeks and returned to Davenport on November 14. Except for brief trips, Bix stayed in Davenport until April 17, 1930 when he went to Chicago and a few days later to New York.

The following information about the Keeley Institute is from the Chrysalis website.

“From Rush, Keeley, and Smith: Three Physicians’ Roles in Alcoholism Treatment

Dr. Leslie E. Keeley, 1834-1900

Dr. Leslie E. Keeley was born in Ireland, raised in New York, and served as a surgeon in the Union Army during the Civil War following his medical education at Rush Medical College in Chicago (named after Benjamin Rush) (22,23).

Through the earlier influence of Benjamin Rush, many in Post-Bellum America considered alcoholism an illness—and alcoholics as persons needing treatment. Alcoholics sought relief through reform clubs and religious movements.

Wealthier addicts received treatment in the nation’s various inebriate asylums—special hospitals for treating alcohol and drug addicts. Numerous alcoholics and their families also experimented with mail order “miracle cures,” which were widely promoted and often promised permanent sobriety from alcoholism in as little as one day (24). In all classes of treatment — religious, psychological, and medical — results varied widely.

In 1879, Keeley, who had developed an interest in drug addiction during his wartime service, announced he had a discovered a specific remedy for alcohol and drug addictions (25). That same year, he opened his first clinic, the Keeley Institute, in Dwight, Illinois and began treating patients with his “Double Chloride of Gold Cure” (26). In accordance with the wishes of its creator, the exact formula of the cure (Keeley hinted only at gold salts in combination with other compounds) was never revealed — a mystery that remains part of the Keeley legacy (27).

The “Keeley Cure” was praised as a miraculous intervention by Keeley’s first patients and later by the popular press (28). White documents Keeley’s uncanny savvy in promoting his cure. In 1891 he issued the following challenge to Joseph Medhill, publisher of the Chicago Tribune : “send me six of the worst drunkards you can find, and in three days, I will sober them up, and in four weeks I will send them back to Chicago sober men.” Medhill responded by sending confirmed alcoholics to the Institute for treatment. When Medhill reported that “they [the men treated] went away sots and returned gentlemen,” news of Keeley’s cure spread throughout the nation and farther. Books by former patients lauding Keeley’s treatment, high profile work with alcoholic veterans of the Civil and Mexican Wars, and aggressive advertising sent patients flocking to the Keeley Institute. Keeley began to franchise and by mid-1893 there were 118 Keeley Institutes in America. Institutes were founded in England, Finland, Denmark, and Sweden as well (29).

Above: post card of the Keeley Institute, circa 1930.

Patients in the Keeley Institutes underwent a four week treatment course. The atmosphere in the clinics was largely informal, with minimal direct supervision of patients. There was a strong mutual support among patients, and patients maintained contact with each other after leaving treatment, often through post-treatment support groups called Keeley Leagues. During the first few days of their therapy, new arrivals were provided with as much liquor as they requested. In fact, the only strictly enforced treatment routines were the four times a day injections of Keeley Cure. At 8 a.m., 12 noon, 5 p.m., and 7:30 p.m. patients received injections drawn in varying amounts from three bottles with red, white, and blue liquids. Independent laboratory tests published in medical journals and the press reported widely different formulas, including ingredients such as alcohol, strychnine, aloe, coca, morphine, atropine, and morphine (30).

Keeley required all of his employees and franchisees to sign a pledge to never reveal the formula of the cure. He received harsh criticism from the scientific establishment (and competitors) for withholding the formula. Keeley’s secrecy prevented scientific peer review and independent replication studies; it gave the Keeley Institutes a monopoly on a potentially important drug. Thus many in medicine viewed Keeley’s secrecy as a serious breach of medical ethics, to which Keeley responded:”…my cure is the result of a system, and cannot be accomplished by the administration of a sovereign remedy. It involves he intelligent use of powerful drugs, gradations to suit the physical condition of particular patients, changes in immediate agents employed at different stages of the cure, and an exact knowledge of the pathologic conditions of drunkenness and their results” (31). Keeley argued that release of the general formula would lead to its gross misuse (32).

Controversy continued to follow Keeley until the end of his life. The Keeley claim of an unprecedented 95% success rate for treatment of alcoholics (later modified to 51%) was hotly challenged. Competitors moved in with other gold cures.”

I am grateful to Chris Smith for kindly sending me the photo of the Institute and the information about Dr. Keeley.

Bix and the Beta Theta Fraternity.

The University of Iowa was founded on February 25, 1847. Almost 78 years later, on February 2, 1925, Bix Beiderbecke enrolled at the University as an “unclassified student.” Within a few days, Bix pledged the Beta Theta Pi Fraternity (Alpha Beta Chapter), the same fraternity that his older brother Burnie had joined while he was a student at the Iowa State University. Bix’s career as a student was short-lived: on February 20, 1925, Bix withdrew from the university. Because of his short stay, Bix was never initiated in the fraternity.

This information is available in Philip and Linda Evans’ book, “Bix: The Leon Bix Beiderbecke Story.” We now have tangible proof of Bix’s pledging. It turns out that Bix, together with the other fourteen pledges in his class, signed his name in the paddle that was presented to the pledge master, Carlyle Fairfax “Andy” Anderson. The paddle signed by Bix is, through a generous gift from Robert G. Anderson, the son of Carlyle Anderson, in the hands of the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Society. In his letter accompanying the gift, Robert writes, “Both my mother and father were at the University of Iowa at this time, and both remember hearing Bix play. They said they never heard anything so beautiful in their lives as the sound that Bix made. My mother remembers him playing on the back of a flat-bed truck that toured around the campus. It is also interesting that she went to summer camp with Bix’s sister. My mother was from Cedar Rapids.”

In p. 183 of Evans and Evans’ “Bix: The Leon Bix Beiderbecke Story”, we read, “Those later Blue Goose dances in the Burkley Hotel were the idea of the center and captain of the team, “Tubby” Griffin. Tubby promoted these dances with another fellow, leasing the ballroom from the hotel and booking the band.” Robert speculates that this “other fellow” might have been his father. Robert writes, “It is entirely possible that this [other fellow] was my father, as I do remember him saying that he put on dances as a way to pay his way thorugh the university. He was also caprtain of the Mason City football team, and although he didn’t play at Iowa, he had some friends on the team, and this woulld fit.”

The Beta Theta Pi Fraternity was founded on August 8, 1839, at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio. Little did Bix know when he pledged Beta Theta Pi, that in May 1971, James Robert Grover would submit “A Creative Aural History Thesis” to the Department of Speech of Miami University, Oxford, Ohio, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. The title of the thesis is “A Series of Nineteen One-Half-Hour Original Tape-Recorded Radio Programs on the Life and Music of Leon Bix Beiderbecke.”

I am grateful to Rich Johnson for kindly sending me photographs of the paddle and a copy of Robert Anderson’s letter.

The Reopening of the Blue Lantern

GRAND RE-OPENING OF THE “BLUE LANTERN” ballroom in the former Hudson Lake Casino, Hudson Lake, Indiana. The same place where Bix played in the summer of 1926 with the Jean Goldkette unit. Enjoy live 20s & 30s-style jazz with the hot & sweet dance music of the West End Jazz Band, Mike Bezin, leader. Further info will follow on the “re-opening date.”

This announcement was included in a message that Fred Smith kindly sent me a few days ago. The Blue Lantern in Hudson Lake was the ballroom where Bix and his fellow musicians spent the “happy summer” of 1926. For information and images about the summer of 1926, go to the following two links. Blue Lantern. Images.

Mike Bezin provided the following information. “I’m committed to helping to make the re-opening event and the Blue Lantern a success, and I really appreciate your interest. I would like to see the idea of musical performances become a reality at Hudson Lake again, not only with our group but others as well.

Our group, the West End Jazz Band, has been active since 1975. In the past two years we have focused on building a repetoire of the arranged hot and sweet dance styles of the late 20s and early 30s. In addition to our interest in Bix, we also have drawn on selections from recordings by the California Ramblers, Coon-Sanders, the early Guy Lombardo, Jelly Roll Morton, Isham Jones, Russ Carlson, and a number of other lesser known groups.

Our current personnel is:

Mike Bezin – cornet, vocals, leader

Leah Bezin – tenor banjo, tenor guitar, vocals

Frank Gualtieri – trombone

John Otto – alto sax & clarinet, vocals

Mike Waldridge – tuba

Wayne Jones – drums

We’re scheduled for several days of recording in October and November that should produce a CD, so that should be available soon. Thanks for your interest and help in making the Blue Lantern’s return to business a success.”

Fred adds the following fact. The musicians “have played several times at Phil Pospychala’s annual March “Tribute to Bix Fest,” under Leah’s direction as “Leah LaBrea and her Flexo Boys.” (Phil seems to like that name!)”

The owners of the Blue Lantern Ballroom plan to have, in about a month, a possible web site for information regarding activities. Look here from time to time for additional information.

I am grateful to Fred Smith for the information he provided and for acting as a liaison to Mike Bezin.

Addendum, 10/5/01. Mike provided the following additional information.

The new incarnation of the Blue Lantern is called “The Whistle Stop.” Already an ice cream parlor is in operation. The website will be launched in a few weeks.

A ten-minute television spot will be aired on the South Bend, Indiana public television station. The spot was produced by Bill Warrick and provides an account of the history of the Blue Lantern, mostly as it relates to Bix.